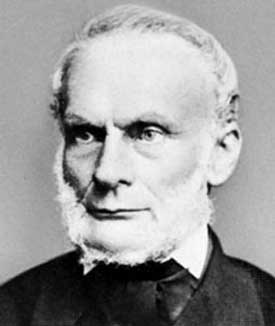

The Master!

Rudolf Clausius

The next name on our list of founders of scientific disciplines is so important, and his accomplishments so profound, that they get a whole page to themselves. In his 1980 book, called: The Tragicomical History of Thermodynamics, 1822 - 1854 historian of science, Clifford Truesdell says of him:

There is no doubt that Clausius with this paper created classical thermodynamics. Compared with his work here, all preceding except Carnot's is of small moment. Clausius exhibits here the quality of a great discoverer: to retain from his predecessors major and minor - in this case, from LaPlace, Poisson, Carnot, Mayer, Helmholtz, and Kelvin - what is sound while frankly discarding the rest, to unite previously disparate theories, and by one simple if drastic change to construct a complete theory that is new yet firmly based upon previous partial successes" Clifford Truesdell

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius, was a man of rare and surpassing genius and insight. His thoughts were so deep that none among his contemporaries - including recognized and highly acclaimed geniuses - understood them. Men who were otherwise giants of society, were mere boys compared to the towering intellect, that was Rudolf Clausius. A humble man, of humble origins, who put himself through school as his parents had run out money raising their other (more than 10) children. For many years, his ideas always bore the burden of ridicule and stiff opposition upon publication: because although he was writing in plain English - no one had any clue what he was talking about. He nonetheless, had the courage of his convictions, and published voluminously on his chosen subject of study, what later came to be called Thermodynamics. Rudolf Clausius is the father and still defining character of Thermodynamics. As Clifford Truesdell commented: "Compared with his work ... all preceding except [Carnot] is of small moment." I would add: all preceding and succeeding - including Maxwell and Boltzmann - are of small moment! For they too, like Kelvin before them, did not understand what Clausius saw so clearly: the irreversible nature of all baryonic processes - and what made them so! As Kathy Joseph says: "With 'Entropy,' Clausius, had given the irreversible action of nature - an equation, and a name." And as you will see, it is his equation that has stood the test of time - not Maxwell's and Boltzmann's!

1850

Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius (2 January 1822 - 24 August 1888) was a genius! Some scientific luminaries are clever, others brilliant and yet others insightful in a way that beggars belief. Clausius had all of those qualities, and more. Like Faraday before him, Clausius was a man whose scientific accomplishments were more a matter of an inborn knack for stupendous thinking, than of formal training: his scientific skills seemingly instinctual - and unerring. However, these gifts were not magical powers. They were, the result, of Clausius' deep powers of logic and his unswerving commitment to the facts! He was a man of quite disposition, whose nature lent itself most easily to deep study and analysis. This meant that where others, looking superficially, saw contradictions and difficulties, Clausius - through his deep insights - saw agreement and cohesion. At a time when Carnot's theory - based as it was on Caloric theory - seemed to be at irreconcilable odds with Joule's assertions about the mechanical equivalent of heat, Clausius realized that, not only where they not contradicting each other, but that they were in essence, complimentary insights. Luminaries like Thomson, and indeed Joule himself, were convinced that the two theories were contradictory and could never be shown to be in agreement. Clausius saw through the confusion, clearly explaining that:

I do not imagine that the difficulties are so great as Thomson considers them to be; for although a certain alteration in our way of regarding the subject is necessary, still I find that this is in no case contradicted by proved facts. It is not even requisite to cast the theory of Carnot overboard; a thing difficult to be resolved upon, inasmuch as experience to a certain extent has shown a surprising coincidence therewith" Rudolf Clausius

Simply put, Clausius, recognized that both Carnot's and Joule's work had merit, in that Joule had produced "proved facts;" and so had Carnot, for: "experience to a certain extent [had] shown a surprising coincidence" with Carnot's theory. Here, Clausius' insight was able to identify that Carnot's theories had only been proven correct to a "certain extent." To what extent? That's what he identified next:

On a nearer view of the case, we find that the new theory is opposed, not to the real fundamental principle of Carnot, but to the addition 'no heat is lost;' for it is quite possible that in the production of work both may take place at the same time; a certain portion of heat may be consumed, and a further portion transmitted from a warm body to a cold one; and both portions may stand in a certain definite relation to the quantity of work produced. This will be made plainer as we proceed" Rudolf Clausius

Why was Clausius confident that "both may take place at the same time?" He realized that heat could simultaneously be transferred from warmer to cooler regions and be getting produced and consumed! But how could that be? The genius of Clausius, was to allow the facts to lead him to counter-intuitive conclusions, that no one else had come to: there must be more than one kind of heat or energy, involved. Before him, all who had considered the issue believed either in Carnot's theory or in Joule's assertions, but not both. And so it was that in 1850, on his very first try, Rudolf Clausius was the first person to formulate a complete version of the first law of thermodynamics. He proposed that:

It follows, therefore ... that the entire quantity of heat, Q, absorbed by the gas during a change of volume and temperature may be decomposed into two portions. One of these, U, which comprises the sensible heat and the heat necessary for interior work, if such be present, fulfils the usual assumption, it is a function of v and t, and is therefore determined by the state of the gas at the beginning and at the end of the alteration; while the other portion ... comprises the heat expended on exterior work" Rudolf Clausius

His equation for this reality was:

U = Uo + Q - W

Where U means total internal energy, Uo means initial internal energy, Q stands for the heat supplied to system, and W for work. This formula is still the formula for the first law of thermodynamics. The terms for internal energy (U and Uo) are now joined and expressed as the change in internal energy (AU), making the updated form of the equation:

AU = Q - W

So pronounced was his ability for discerning subtlety, that for years, accomplished men of science - great scientists in their own right failed to grasp the essence of his papers and glumly insisted that he was plagiarizing their ideas, or ideas that had already been proposed by others. Some who fell into that category were Lord Kelvin, William Rankine and Herman von Helmoltz. Nothing could have been farther from the truth! What Clausius brought to the party was unique, innovative and groundbreaking. It took years, even for the brilliant minds just mentioned, to come to appreciate his genius and the singular exceptionalism of his scientific insights. Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius was a genius!

Clausius was the youngest of eighteen children! and had to put himself through school as his parents had run out of money by the time he was ready for tertiary education. He did so uncomplainingly, by working as a high school teacher - having dropped out of university at 21. It wouldn't be long before the enterprising maverick would make his mark on the scientific world. Six years later, Clausius was introduced to the foundational ideas of Sadi Carnot. Emile Clapeyron was not the only scientist to write about and try to expand on Carnot's breakthrough ideas. Another to do so was the formidable Lord Kelvin. Kelvin's interest in the subject had to do with his desire to develop the aforementioned absolute temperature scale, by acquiring a deep understanding of thermodynamics, and applying the principles gleaned from that knowledge in developing his temperature scale. Where Kelvin did not see any flaws in Carnot's theory of heat, Clausius was not only able to discern that something was wrong, but was able to identify where Carnot's theory went too far and where it didn't go far enough. First, where Carnot overreached. The secret to Clausius incisive mind was his ability for the deep, intensive thinking out of problems. He fully traced out the consequences of theories, and was thus able to differentiate between logical and illogical assertions, between empty reasonings and those that agreed with the facts. From his very first paper, he grasped the truthfulness of the mechanical equivalent of heat. Remember that even with Joule's strong assertions to that fact, Thomson was not convinced. Clausius on the other hand was able to grasp the concept from the original work of Carnot! His first sentence in his 1850 paper On the Motive Power of Heat, and on the Laws Which can be Deduced from it for the Theory of Heat, he writes:

Since heat was first used as a motive power in the steam-engine, thereby suggesting from practice that a certain quantity of work may be treated as equivalent to the heart needed to produce it, it was natural to assume also in theory a definite relation between a quantity of heat and the work which in any possible way can be produced by it, and to use this relation in drawing conclusions about the nature and the laws of heat itself" Rudolf Clausius

Secondly, consider the subject of heat being a caloric (ether),

If it be assumed that heat, like a substance, cannot diminish in quantity, it must also be assumed that it cannot increase. It is, however, almost impossible to explain the heat produced by friction except as an increase in the quantity of heat. The careful investigations of Joule, in which heat is produced in several different ways by the application of mechanical work, have almost certainly proved not only the possibility of increasing the quantity of heat in any circumstances but also the law that the quantity of heat developed is proportional to the work expended in the operation. To this must be added that other facts have lately become known which support the view, that heat is not a substance, but consists in a motion of the least parts of bodies" Rudolf Clausius

Hence, Clausius already in 1850, only a year after first hearing of the discipline of thermodynamics had a clear understanding of its principles. He had the availability of established facts to help him reach logical conclusions. Notice that he again emphasizes that heat is not a substance, but rather, the product of atoms or molecules in motion. That is what the phrase: "consists in a motion of the least parts of bodies " means. It is referring to the smallest structures in elements, be they atoms as in hydrogen, or molecules as in water. No one in Clausius' times had dreamt of subatomic particles.

Heat was not a material substance, but rather a form of energy. I say 'energy,' but in 1850 Clausius used the term: "vis viva," as the word 'energy' was not yet in popular use, even though it was coined over four decades earlier, by Young.

The following year, 28 year old Clausius published a paper - in what would prove to be the first of nine - on the subject of heat and its dynamics.

1854 - Why the 2nd Law of Thermodynamics Had to Modified

As stated by Clausius, the second law was incomplete, because it failed to show the true nature of the theory and it also failed to show its connection with the FIRST LAW. (from 5:40 onwards - Entropy).

The problem with Carnot's theory, as groundbreaking as it was is that it was designed to show how an ideal engine works. That in turn meant, in order to make its real world applications clear, something needed to be added to it. That is what Clausius meant when he said:

... the theorem, is incomplete, because we cannot recognize therein, with sufficient clearness, the real nature of the theorem, and its connexion with the first fundamental theoremRudolf Clausius

What did that mean? Why did Clausius feel that Carnot's efforts lacked "sufficient clearness?" Carnot's ideal heat engine, recognized that heat caused work and that for such heat to be effective there had to be a temperature difference between the two heat sources, without which, no heat would transfer and no work could be done. In fact, the efficiency of heat engines is tied to this temperature difference: the higher the temperature difference, the more efficient the engine. This, is all true. So what was missing? And why would the absence of this missing factor 1) make the theory "incomplete" and 2) make it hard to recognize Carnot's theory's "connexion with the first fundamental theorem?" Carnot's theory identified heat and temperature, but missed altogether a third - less obvious - component, which is as integral to energy, as energy is to work. Just like you cannot do work without energy, you cannot transfer energy without transferring this factor. Let's examine his thinking.

We have an advantage over Clausius, not only in that we know what he did and how he accomplished it, but we have seen this exact type of reasoning before. The method Clausius used was the same one used by Kepler, for deriving his three laws of planetary motion from Brahe's remarkable tables of observations. It is similar to the one used by the different contributors to the combined gas law. In figuring out how the parameters relate to each other, hidden connections are exposed, as in the case of Robert Boyle, whose analysis of the pressure and volume of a gas led him to discover that their product is a constant! In a word then, what we are looking for from Clausius mathematical proofs is a ratio. It is this ratio that comprises the link, Carnot missed.

A peculiar feature of Carnot's ideal engine was that the ratio of the incoming heat and the outgoing heat was equal to the ratio of the temperature of the hotter reservoir to the temperature of the lower reservoir. Again the mathematics is straightforward and simple. The equations of the ratios follow below:

e = 1 - Qo /Qi

e = 1 - To /Ti

Since both ratios are equal, we can combine them and express the reality this way:

To /Ti = Qo /Qi

With a slight rearrangement of the terms through cross-multiplication, the equation becomes:

Qi /Ti = Qo /To

This empirical equation of a ratio cannot represent either heat or temperature, since they are both variables of the equation. So what entity does this ratio represent? As Caltech professor, David Goodstein, once said:

In other words, something that goes in, is the same when it comes out. If it's not the heat, and if it's not the temperature, what is it? It's the heat divided by the temperature at which it flows, and according to Clausius that's ENTROPY!" Professor David Goodstein

Understanding what Clausius next did with Entropy, in his quite and methodical style, is fundamental to understanding, not only what was missing in Carnot's original theory, but understanding how it completes the second law of thermodynamics, and connects all to the laws of thermodynamics! This in turn, will give us a firm understanding of the true structure and functions of the universe as a whole. Yes. It is that important! Thermodynamics as a scientific field sets the parameters of the physical universe. The zeroeth law defines temperature in a non circular way, which means without having to reference heat. The first law is about the mechanical equivalent of heat and is an expression of the law of the conservation of energy. The second law is the about entropy and the irreversibility of natural processes. It is this law that gives us the one way arrow of time! The fourth law, sets the minimum parameter to physical existence, by establishing an absolute lower threshold - a temperature that no physical substance can attain. Hence, understanding thermodynamics is critical to understanding the universe, and we cannot come to understand the science behind reality without it. It is for all of these reasons that Clausius entitled his fourth paper on thermodynamics, published in 1854 - barely five years after he first got acquainted with the field: On a Modified form of the Second Fundamental Theorem in the Mechanical Theory of Heat. In it Clausius took Carnot's thought experiments about the ideal heat engine and modified them, expressing them within the physical confines of the natural world. He ran a mental experiment, that took Carnot's assumptions to their logical conclusions - in the real world. His incisive mind then preserved only what had been proven to be true, by experiment and through observed facts, and discarded any, and all fluff. How did he do it?

Originally, Carnot's thought experiment, was to model the perfect machine. Recall that his motivation was patriotism, and he thought any breakthroughs would catapult France into dominance in the industrial revolution. As such, he had conceived of a perfect engine, one that could use heat to produce work when run in one direction, and then, when run in the opposite direction, it would use work to produce heat - it was reversible! How did it work? The operation was simple enough. We understand about the need for a temperature difference between the two heat reservoirs, but the ideal in Carnot's 'ideal heat engine,' had to do with the engine itself. It was in the workings of the engine that, in his search for ultimate efficiency, Carnot suspended reality. He made all the processes inside the engine theoretical, instead of realistic. Inside his engine heat suddenly didn't need a temperature difference to transfer from one place to another. When moving parts rubbed against each other there was no friction, and since there was no friction, moving parts didn't create or exchange heat with their surroundings. All three of these conditions do not occur in nature. Thus Carnot's engine only works in our minds as a thought experiment. That is why Goodstein comments:

Sadi Carnot's greatest ideas never worked!Professor David Goodstein

Of course, that is not the whole story. Carnot was brilliant! And he was starting with a blank sheet of paper: before him, there was no science called Thermodynamics. He had to build his ideas from the ground up. Had his life not been cut so horribly short, he would certainly have refined his ideas, starting from the most theoretically efficient idea and honing down to the most effective, under real world conditions. Nevertheless, his premature death meant others would have to develop the science going forward.

What made Carnot's engine perfect? Because it was theoretically ideal - meaning it couldn't be built in the real world: its dynamics could be defined according to conditions that never occur in real life. Part of the appeal of such an exercise, was that it defined the parts that any engine must have to operate. Those are: 1) a heat source: a reservoir of hot temperature, where heat is transferred from, to fuel the engine 2) the engine itself, that does the work and rejects unused heat as exhaust to 3) a cold sink, where unused heat (waste heat) is transferred to. Without the two reservoirs at different temperatures heat cannot transfer, and no work can be done! All of that is true under real world conditions. So what made Carnot's engine theoretically ideal, or put another way: what made it not real?

The fact that you need two reservoirs of heat, which are at different temperatures, is right. The fact that there must be an engine in the system that uses heat from the hot reservoir to do work and some leftover heat is sent to the cold sink (the lower heat reservoir) is also true. What was imaginary, was how Carnot defined how the engine itself, works. He did this in three ways that do not occur in real life. Let us review them one by one. Firstly, he described the engine doing work without a temperature difference. In other words, as the engine was going through its processes the heat stayed at the same temperature. Scientists call this kind of process isothermal. That word is taken from the Greek terms isos, which means "equal or identical," and therme, which means "heat." Hence, isothermal means a process which operating at an identical temperature throughout. To be sure, technically, there are isothermal processes in nature. When an element undergoes a phase transition, say from a solid to a liquid, the temperature stays the same - even as heat is being added - until all the molecules have transitioned from their solid state into their liquid state. Of course, in this process, the additional heat doesn't change the temperature because it is used to break the bonds holding the atoms or molecules together. Hence, after a phase transition, there are always additional degrees of freedom available to the atoms in their new state, as more bonds have just been broken. So while the temperature stays the same, we understand where the additional heat is going to, and what it is accomplishing. Carnot's engine is different. In it heat transfers without a difference in temperature. Something that we know is impossible, hence this feature of the engine is theoretical, or not real.

Secondly, the gas expands pushing a piston without exchanging any heat with its surroundings. In the words, the gas increases in volume without without taking any heat from, or giving any heat to its surroundings. Again, something that does not happen in real life. Scientists call this kind of process adiabatic. This word is also taken from Greek. Adiabatos meaning "not to be passed," a means "not," and diabatos "to be crossed or passed." Thus, adiabatic: "refers to a process in which no heat is transferred into or out of a system, and the change in internal energy is only done by work." When we put these two factors together we see why Carnot's energy cannot work under real conditions. There is no work done because the temperature stays the same - isothermal. Secondly, the engine does not transfer any heat with its surrounding, which we all know does not happen in real life. For instance, when you arrive home and turn your car engine off, put your hand on the hood and you can feel the heat of the engine being transferred to the surroundings. Anyone who rides a motorbike knows that engines transfer heat to their surroundings. They can feel it on their legs. Or run outside until you start to sweat. Your sweat is your body - the engine - transferring heat with its surroundings. We should all have a firm grasp of how this works now. Carnot's engine does not work, because it does not follow these natural laws, of how real engines work.

Thirdly, he discounted friction. Friction occurs whenever an engine has moving parts. In Carnot's ideal engine, the parts moved without producing friction. Friction in turn creates heat. And as we know, in the real world, heat has an immediate effect on the volume and pressure of a gas. All three of the above detailed factors are known as losses in thermodynamics. That's because, as Professor Goodstein puts it:

In real engines heat flow isn't isothermal, power strokes aren't adiabatic, and there's always friction between moving partsProfessor David Goodstein

All of that is to say, the factors Carnot discounted, are the very factors thermodynamics shows to be what makes real engines, real! Hence, the inescapable conclusion is once again expressed best by re-quoting Professor Goodstein's earlier words:

Sadi Carnot's greatest ideas never worked!Professor David Goodstein

That's not to discredit Sadi Carnot's efforts in any way! On the contrary, Carnot was a brilliant engineer and his accomplishments in creating the "ideal" engine were instrumental to both the establishment of thermodynamics as a science and to the field of engineering. A scene from 2007s Transformers movie illustrates the point well. In Hollywood fantasy the "perfect engine" from which hi-tech machines were reverse engineered is Megatron - the leader of an alien race of AI robots. In real life, that perfect engine is an theoretical ideal whose characteristics were defined by one - Nicolas Léonard Sadi Carnot. It was his intention for his engine to be an 'ideal' machine. As such, the purpose of highlighting the futility of trying to build a Carnot engine in real life, is not to disparage its talented inventor, but rather, to show that such an attempt would be an effort to break all the laws of real engines: the laws of thermodynamics! The fact that it is not possible to build Carnot's engine in reality, does not reduce its value as a guiding parameter for engineers trying to build the most efficient engines. It is fundamental to understanding what is possible, and impossible, in the world of thermodynamics.

For a concept that has such a large impact on the world, its simplicity of operation is surprising. It is comprised of four simple and reversible processes: two where the ideal gas expands against a piston, and two where the ideal gas is compressed by the piston. Since, all four processes are reversible, the Carnot cycle as a whole is reversible, which means we can start at any stage in describing it. We will start with isothermal expansion: where the ideal gas receives heat from the hot temperature reservoir and expands while maintaining the same temperature. Next, in this second of the four mini processes, the heat source is removed and the gas continues expanding against the piston. No heat is transferred in or out with the surroundings, and the technical name for that is an adiabatic expansion. The last two mini-processes are just the opposite of the first two and are also reversible. In thermodynamics, whenever work is said to be done, it means the entity doing the work is pushing against something else. Hence, in the third mini-process, a cold heat sink is placed against the gas and heat is transferred from the gas to the cold sink without a change in temperature in the gas. A corresponding compression of the gas occurs, as the piston does work on the gas. Since, there is no change in temperature while a gas being compressed, it is called an isothermal compression. Lastly, in the fourth mini-process, the the cold sink is taken away and the compression of the gas continues without any heat interactions between the system and its surroundings. This as you may have guessed is called an adiabatic compression. The Carnot cycle ends here, as the system as a whole is at its original starting point.

Carnot's ideal heat engine removed all real life losses from the functions of engines. The discounting of real world conditions is what makes building a Carnot heat engine impossible! It cannot be built in real life. For instance, in real life there is always friction between moving parts; the transfer of heat always demands a temperature difference between a hotter heat source and a colder heat sink; and mechanical heat strokes (the movement of a piston) always involves the transfer of heat either into or out of the system, that it they are never adiabatic. the pistons in his engine did not have friction. That resulted in the physically impossible and logically inconsistent conclusion that not only was energy conserved but entropy was too. All humans, including small children, know instinctively that this is untrue - even if we can't explain it scientifically. If you were to be shown a video of a regular glass of water on a porch or patio in summer, and as the video kept running, suddenly ice cubes started forming in the glass of water, what would your explanation be? Everyone knows the answer instinctively. The video is running backwards! That is true, because of the one way arrow of time. The one-way arrow of time only exists because energy and entropy are not equal, hence the first and second laws of thermodynamics are: 1) The energy of the universe is constant and 2) The entropy of the universe tends towards a maximum. That shows that between energy and entropy, the 'law of conservation' applies only to energy and not to entropy. Otherwise both quantities would be constant in the universe! The problem that now presented itself to Clausius, was how to prove the falsity of Carnot's result for ideal engines, and that proof is what separates the real from the ideal! It is critically important!

Carnot's ideal engine was a reversible one, called the Carnot cycle. That meant that its components would be in the same state at the end of the process as they were at the beginning.

The importance of Clausius' work was that it showed the limitations of the first law of thermodynamics. In all the experiments Joule conducted, he found evidence for a conservation law. That law of conservation was not for mass, but rather, for the conservation of energy! It was the fact that heat could be created and destroyed, that proved that it was not a substance, but a form of energy. Conservation of energy, means whenever there is an interaction of energy, it must proceed in a balanced way. The amount of energy before and after the process must be equal - in different forms, but the quantity must be equal. That was the value of Joule's experiments. Each time he measured the energy interaction he found an exact equivalence. It didn't matter whether he was measuring the amount of chemical energy produced by his battery compared with the heat it produced in the electrical wire, or if he was measuring the amount of electricity produced versus the amount of hydrogen that was decomposed in electrolysis, or even when he used gravitational energy to drive a paddle wheel and measured the amount of heat that generated in water. In all cases Joule's empirical experiments proved the mechanical equivalent of heat, and did much to establish the field of thermodynamics. Hence, many lauded his accomplishments, including Feynman, who wrote:

There is a fact, or if you wish, a law, governing all natural phenomena that are known to date. There is no known exception to this law - it is exact so far as we know. The law is called the conservation of energy. It states that there is a certain quantity, which we call energy ... which does not change when something happens. It is not a description of a mechanism, or anything concrete; it is just a strange fact that we can calculate some number and when we finish watching nature go through her tricks and calculate the number again, it is the same" Richard P Feynman

When the first law of thermodynamics was added to the second law - as the second law was discovered first, if you remember - no one noticed that there was a contradiction between them. Everyone imagined they complemented each other fully, perhaps due to the word equivalent. Everyone until Clausius. The equivalence between mechanical energy - work - and heat does not mean that you can fully convert one into the other, only that whenever there is an energy interaction, you will always have the same amount of energy after you have finished the interaction, as you did before you started it. Only work can fully be converted into heat. Heat can never be fully converted into work. That truth was not self-evident. That is what Clausius meant when he said Carnot's theory was, "incomplete." Hence, his need to publish a paper in 1854 titled On a Modified Form of the Second Fundamental Theorem in the Mechanical Theory of Heat, in which he eliminated the contradiction and brought the two laws into harmony. This is how he proved it.

Since Carnot's heat engine is theoretical, and not real, you can't actually run the reversible Carnot cycles forward and backwards to see what they produce. But you can work out their consequences logically, as Clausius next did. Without the ability to conduct practical experiments, Clausius knew he would have to prove the consequences of the Carnot cycle by working out its mathematical implications. The Carnot engine was essentially a transformation machine, that turned heat into work if you run it in one direction, and converts work into heat if you run it in the opposite direction. He thus set himself the task of mapping these transformations out numerically. His guiding principle was that heat, on its own, only travels in one direction - from hot to cold! In mathematics direction is signified by positive and negative, as in the the number line, where right of zero is positive and left of zero is negative. He thus employed bulletproof logic in formulating his mathematical analysis of Carnot's reversible transformations. Since they were reversible, the sum of both transformations, in both directions should always be positive at all times. Otherwise, it would mean a transformation was powered by heat going, on its own, from cold to hot - a thermodynamic impossibility, through the original (second) law of thermodynamics. To understand this clearly, we must distinguish between reversible and heat traveling in the wrong direction. Think of yourself as representing such energy interactions. When you walk forwards, that is like heat transferring from hot to cold - positive. If you walk backwards, that is heat doing something impossible for it to do on its own - travel from a cold to a hot reservoir: negative. So in your mimicking of heat you can only walk forwards. How, then, would you act out two reversible transformations of equal value. Let's say the one transformation involved you walking five steps in one direction; its opposite, the reverse transformation would need you to walk five steps in the opposite direction without walking backwards. How could you do that? By turning around 180 degrees after the first five steps and then walking five steps in the opposite direction - toward your original position. Now all your steps are mathematically correct and you've followed the laws of thermodynamics. In other words, at no time did you contradict the laws of thermodynamics. That - in a nutshell - is what Clausius did with his mathematical formula. The deeper mathematical details are available online, for those so inclined*; here, I have merely summarized the development of his ideas, to give you only his conclusions. Careful attention must be paid to his wording. It will be clear from the following quote that he calculated the implications for both reversible and irreversible transformations. His conclusion, includes a principle that applies to one and not the other, and another principle that applies to both reversible and irreversible cyclical processes. We must be careful to apply the distinctions as clearly as he intended us to. For that reason, I have separated the quote into its two relevant parts to make the distinctions clearer:

In the proof of the previous theorem, that in any reversible cyclical process, however complicated, the algebraical sum of all the transformations must be zero, it was first shown that the sum could not be negative, and afterwards that it could not be positive, for if so it would only be necessary to reverse the process in order to obtain a negative sum." Rudolf Clausius

(I appreciate that the adults will easily make the distinction, but a big part of this publication is making it easy for even children to understand, and it is for them, that extended explanations are given, in an effort to make everything as clear as possible. I thank the adults for their patience.) The second part of the quote is where its gets a bit trickier, because he divides the above quote and applies it selectively. That is, he applies: "it was shown that the sum could not be negative," to both reversible and irreversible processes. However, Clausius says the second part, which starts with: "and afterwards ..." cannot apply to irreversible processes:

The first part of this proof remains unchanged even when the process is not reversible; the second part, however, cannot be applied in such a case. Hence we obtain the following theorem, which applies generally to all cyclical processes, those that are reversible forming the limit: The algebraical sum of all transformations occurring in a cyclical process can only be positive" Rudolf Clausius

The MAIN Point

Why do reversible processes form the limit? All cyclical processes are positive, but "reversible" ones must be limited to being neither positive, nor negative. They can only ever have the sum of ZERO! Why? If you run a reversible process forward and it gives a negative sum, it means energy was being spontaneously transferred from cold to hot - which is impossible. If you run a reversible transformation forward and it gives a positive sum, all you would need to do, to get a negative result, is run it in reverse - since it is reversible! But that would violate the laws of thermodynamics. Hence, the sum for all reversible transformations must always equal zero. For transformations that cannot be reversed, there is no restriction against them having sums that are positive, because since the transformation is by definition irreversible, there is no way to turn the positive result into a negative. Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius was a genius!

That was highly significant, because it was only when Clausius analyzed reversible heat transformations, that humans discovered LIMITATIONS! In other words, the energy that drives reality is limited to irreversible transformations. We can now understand why the arrow of time points in only one direction: FORWARD. That is true for all spontaneous transformations. Of course, non-spontaneous transformations are possible and they happen everyday: but they need an external source of energy to progress. They need a helping hand. They cannot happen on their own, as we have previously defined. Examples abound: i.e., refrigerators, that can be used to make heat move from cold (inside the fridge) to hotter reservoirs (the surroundings, through heat released from the back of the fridge). In all such cases, an external force is needed. In the case of a fridge, that force would be the electricity it draws when plugged in. Of course, humans will never be able to create a refrigerator for the universe as a whole, which is what it would take to make time move backwards. If you ever hear scientists wonder about how to make time travel possible, never listen! They don't understand the basics of Physics! The four laws of Thermodynamics are fundamental to all other sciences, and only someone who doesn't fully understand the second law - entropy, would ever suggest or waste time thinking up strategies about how to reverse the arrow of time. Clausius did say that the second law of thermodynamics was "much more difficult to understand, than the first." There are many reasons for this limitation, not just technical. However, we will illuminate only one: in such a scenario, if the universe as a whole was the closed system that the theoretical refrigerator (time machine), was working on, what would serve as the "surroundings," to which the transferred heat would need to be moved to? Recall that if there is no temperature difference there is no transfer of heat, hence no work. If the inside of the fridge represents the universe, what would the outside of the fridge be represented by? The universe is everything that exists, and it, by definition, CANNOT have a surrounding. Hence no such process could be engineered, irrespective of the technical impossibilities involved in attempting to do so.

Recall that Clausius' misgivings about the incompleteness of Carnot's theorem were not limited just to the lack of, "sufficient clearness," as to the "real nature of the theorem," but also to its lack of "connexion with the first fundamental theorem." So the full impact of Clausius discovery is not only that time moves in one direction, but that it does so because of the nature of the "first theorem," or the first law of thermodynamics. That is, because energy is conserved - and not heat. If heat were conserved in the form of the ether Phlogiston, energy could not be transformed from one form to another - for heat, and not energy would be the conserved entity! The only way heat can create work, and work can create heat is if heat can be destroyed (consumed), and created (through processes like friction). This makes the equivalence of work and heat an empirical proof that the eternal ether known variously as Phlogiston and Caloric does not exist. As a refresher, here is the definition of the first law of thermodynamics, Clausius refers to:

The first law of thermodynamics is a version of the law of conservation of energy, adapted for thermodynamic processes. In general, the conservation law states that the total energy of an isolated system is constant; energy can be transformed from one form to another, but can be neither created nor destroyed" Laws of Thermodynamics - Wikipedia

The "equivalent values" Clausius had been working to express mathematically, were what he eventually named: "Entropy." Entropy, as has been proven experimentally time and time again, transfers with energy. As Professor Goodstein of Caltech put it: "Wherever energy flows, entropy flows." For,

... the generation of the quantity of heat Q of the temperature t from work, has the equivalence-value ...

Q/T,

... and the passage of the quantity of heat Q from the temperature t1 to the temperature t2, has the equivalence-value

Q(1/T2 - 1/T1),

wherein T is a function of the temperature, independent of the nature of the process by which the transformation is effectedRudolf Clausius

This section is vitally important. In the above quotes, Clausius is telling us three things in the quite manner, that was the essence of his nature. It is why it took his detractors so many years to finally understand what he was saying - and that he was right. Even when they did see the truthfulness of his arguments, they lamented as did Lord Kelvin, that his "hypothesis is so mixed that the general point is lost." Even then - as Lord Kelvin - Thomson didn't grasp the subtlety of what Clausius was explaining so clearly. So, if you blink, you'll miss the three fundamental principles he is trying to teach us about the cosmos. First: the generation of a quantity of heat from work, has an equivalence-value. Second: when heat is transferred, that is, when it moves from a hotter to a colder reservoir (t1 to t2), there is also an accompanying equivalence-value (that moves with it - as Professor Goodstein outlines). Third: and perhaps most importantly, T is a function of the temperature, independent of the nature of the process by which the transformation is effected. That is, the generation of equivalence-values is a state function of the temperature, and only the temperature! Again, a state function is a function that only depends on the beginning and end states, not on the path that was taken to get from one to the other. As Professor Goodstein, so clearly makes the case:

Day in, day out, mother nature's machines crank out entropy; and nobody on earth can compete with her output. Every body of matter, everywhere in the universe contains a certain amount of entropy

The conclusion?

It isn't too hard to tell when entropy flows from one body to another. If heat flows out of a body at temperature T, the entropy of the body decreases by Q over T

AS = Q/T

If heat flows in at temperature T, the body's entropy increases by that amount. Throughout the cosmos when and where heat flows, entropy flows with it. All engines extract heat from somewhere - the sun perhaps, or the boiler of a ship - use some of it to do their work, and then release the rest.... Engines designed by humans, operate pretty much the same way as the ones mother nature cooks up.... As long as heat flows, as long as a warm body is warmer than the cool one, entropy will increase. And it will continue to increase until nothing else can possibly happen. The state of equilibrium. And should that happen, entropy would increase no more. In other words the state of equilibrium, is the state of maximum entropy!" Professor David Goodstein

The formula he derived to express his findings was, firstly for the "generation of the quantity of heat Q of the temperature t from work, has the equivalence-value"

Q/T

Then recall that he summed up the transformations. In his own words: "... the total value N of all the transformations will be"

N = Q1/T1 + Q2/T2 + Q3/T3 + &c... = SUM Q/T

What the above means, is that whenever there are more than two transformations, the total number of transformations will be represented by the letter N, and N will be equal to the sum of all those transformations represented by SUM Q/T. At this stage of its development the equation is:

N = SUM Q/T

The assumption Clausius made in coming up with these formulas was:

It is here assumed that the temperatures of the bodies K1, K2, K3, &c. are constant.... When one of the bodies, however ... changes its temperature during the process so considerably that the variation demands consideration, then for each element of heat dQ we must employ that temperature which the body possessed at the time it received it, whereby an integration will be necessary. For the sake of generality, let us assume that this is the case with all the bodies; then the foregoing equation will assume the form" Rudolf Clausius

N = f dQ/T,

Physicists like to work with ideals because that simplifies their equations and ideals are often so close to the actual, that the small differences can be neglected. That for instance, was what we understood when we learnt that the atomic theory gases uses an ideal gas as its sample gas. The 'ideal gas' is close enough that it mimics the behaviour of all real gases. It is only when there are significant divergencies from the norm that, such deviations "demand consideration." For such cases Clausius created the symbol dQ and used the universal sign convention of f, for integration. For clarity's sake, we again repeat the equation in every day speech. The total amount of transformations N will be equal to the integral of an "element of heat" that changed its temperature "during the process ... considerably" fdQ over temperature T. As Kathy Joseph says: "this function, the heat over the absolute temperature is the equation for entropy." Lastly we recall that Clausius said all such transformations must equal ... zero. Again, in his own words:

Consequently the equation

fdQ/T = 0

is the analytical expression, for all reversible cyclical processes, of the second fundamental theorem in the mechanical theory of heatRudolf Clausius

In an 1855, paper entitled On the Application of the Theorem of the Equivalence of Transformations to Interior Work, Clausius reviewed the developments of his ideas:

In a memoir published in the year 1854, wherein I sought to simplify to some extent the form of the developments I had previously published, I deduced, from my fundamental proposition that heat cannot, by itself, pass from a colder into a warmer body" Rudolf Clausius

That conclusion was Clausius' version of the second law of thermodynamics! As Kathy Joseph says: "Clausius based his ideas of ... equivalence-values, on the the principle that heat cannot flow from a cold object to warmer object, by itself." In 1863 Clausius starting calling equivalence values, by a new name - Entropy! Commentators always say they don't know why Clausius gave Entropy, the letter designation 'S.' However it seems plain from his words below, that it was because he thought the two quantities energy and entropy to be so similar. Judge for yourself:

I propose to call the magnitude S the entropy of the body, from the Greek word ... transformation. I have intentionally formed the word entropy so as to be as similar as possible to the word energy; for the two magnitudes to be denoted by these words are so nearly allied in their physical meanings, that a certain similarity in designation appears to be desirable" Rudolf Clausius

Entropy is a difficult subject and other physicists have struggled with its meaning and significance over the years. For this reason, over the years, many have described it as a form of disorder. It is not. For the simple reason that humans cannot project their thinking onto nature. Each phase of matter has its purposes and this utility has nothing to do with how humans classify the subatomic structure of elements. Would you rather take a shower with some disordered water, or a more highly ordered block of ice. In turn, water, in its liquid state is more highly ordered than air, but which would you rather breath in? Breathing water is called drowning. Oxygen gas, exists in the least ordered of all three phases of matter, but that's the form in which it is most useful to us! The point is all phases of matter have specific uses for which no other state of matter will do! Of course, those who adhere to statistical thermodynamics will object, saying disorder doesn't directly translate to uselessness. The aim of the classification is to measure the probability of finding the subatomic particles of an element or substance in one configuration or another. This too is in error as we shall soon see. Thinking of entropy as a measure of disorder was introduced and championed by two men who built upon Clausius work in error. In trying to get a firm grasp of the essence of entropy, many have tried different descriptions. It was Max Planck who came up with an alternate mathematical formula that tried to describe entropy in relation to the internal configuration of the atoms or molecules involved, instead of following in the understanding pioneered by Clausius. Bizarrely - through an accident of history that is superfluous to our interests - it is known as Boltzmann's equation. It is:

S = k log W

This way of thinking of entropy describes it in terms of micro and macro-states. Microstates relate to structure on the atomic scale, whilst macro-state refers to the large scale properties of the system under consideration. These are properties such as temperature, volume and pressure. Adherents of the newer formula look at it as a more fundamental approach to understanding entropy they use statistical thermodynamics to measure entropy. Since there are too many particles involved at the atomic level of substances, humans can never keep track of each particle. Thus, they use statistics to arrive at conclusions. While this version of entropy has great merit as it looks at elements on a smaller scale, it is in no way more fundamental than Clausius conception of entropy.

1862

The 3RD Law of Thermodynamics

An important common factor between all the early innovators who understood the concept of the 'mechanical equivalent of heat,' was a strong belief in and more or less clear understanding of atomic theory, that is, that elements are made of atoms and it is the motion of the atoms that causes heat. From Count Rumford who recognized this fact when, in boring cannons he realized that it was the friction between his drill and the metal that created heat, to Mayer, to Joule. As for Lord Kelvin, when he finally understood the fundamental flaws of Caloric theory, he changed his mind: whereas, he titled his 1849 paper, On the Motive Power of Heat; to tha partial title of his 1851 paper being On the Dynamical Theory of Heat ...! The change in description from motive power of heat, to dynamical theory of heat is huge. It also follows closely from his changing from calling the subject of energy "An Account of Carnot's Theory of ... Heat ...." to rightly referring to it as "Heat," for Carnot's account of the subject was wrong due to his basic misunderstanding of what heat was. What was responsible for it? Evidence. Evidence, based largely on the experiments of Joule in establishing the "equivalent of a thermal unit of heat," and the results of Regnaults extensive experiments with measuring the properties of gases. The genius of Kelvin was to put the two sets of empirical evidence together and meld the results into a cohesive account of the true nature of how heat affects gases. A scale based on such an idea would not have its dynamics based on the properties of arbitrary gas, but on the dynamics of all gases, and would thus be universally applicable. It wouldn't be a scale that measured the properties of one substance or element, then gauged all other elements or substances against that reference point, but based as it is on thermodynamics itself, it would form the absolute backdrop against which all substances and elements could be measured! Thus was born the absolute Kelvin scale. Kelvin's full title of the first of five papers, he published from March 1851 -1855 on the subject was: On the Dynamical Theory of Heat, with Numerical Results Deduced from Mr. Joule's Equivalent of a Thermal Unit, and M Regnault's Observations on Steam. The scientific lesson? Basing our conclusions on empirical results, even when those results go to our long-held or cherished beliefs, is the value of the scientific method. And the only proper definition of: Science! It shows that Kelvin had now come to appreciate how heat transferred from one substance to another, from hotter regions to colder ones. It was not as a substance that flowed within an element or between elements, but rather, through the dynamical motion of the atoms within elements themselves! As in all cases, appreciating the true nature of heat depended on a clear understanding of the structure of elements - it depended on understanding basic atomic theory. Yet again, Clausius' insights proved far keener than his contemporaries:

Now the effect of heat always tends to loosen the connexion between the molecules, and so to increase their mean distances from one another. In order to be able to represent this mathematically, we will express the degree in which the molecules of a body are separated from each other, by introducing a new magnitude, which we will call the disgregation of the body, and by help of which we can define the effect of heat as simply tending to increase disgregation" Rudolf Clausius

One's ability to comprehend the abstract inner workings of atomic dynamics is the premier resource one needs to have any understanding of entropy. Note the difference between Carnot and Clausius in their understanding of how heat effects the inner dynamics of elements. First we consider Carnot's take on the subject, remembering that he considered heat to be a substance that cannot be diminished or increased in quantity:

... When a body has experienced any changes, and when after a certain number of transformations it returns to precisely its original state, that is, to that state considered in respect to density, to temperature, to mode of aggregation, let us suppose, I say that this body is found to contain the same quantity of heat that it contained at first, or else that the quantities of heat absorbed or set free in these different transformations are compensated .... This fact has never been called into question ... to deny this would overthrow the whole theory of heat to which it serves as a basis" Sadi Carnot - Wiki

Let us spend a few moments parsing out the meaning of Carnot's words before considering what Clausius had to say. We start, by defining the term "aggregate." Merriam-Webster defines it as: "formed by the collection of units or particles into a body, mass, or amount." So firstly we acknowledge that both Carnot and Clausius agreed with Lavoisier's theory, about elements being composed smaller particles - what came to be known as the atomic theory. The collection of these subatomic particles in elements happens in a structured way called lattices. Such lattices, or arrangements within elements are what is referred to by the phrase: "mode of aggregation." The mode is the lattice; the aggregation, is the fact that the whole is made up of many, many particles. Carnot believed that one of his complete cycles represented a body undergoing changes until: "... after a certain number of transformations it returns to precisely its original state ... in respect to ... mode of aggregation ... this body is found to contain the same quantity of heat that it contained at first ...." This is the crux of Carnot's error! Since, he believed heat to be a substance that was always conserved, then its presence in an element or substance, caused changes to the internal particles of that element or substance. The error is that Carnot attributed these internal changes to the heat itself not to the atoms or molecules. This is why his paper of 1824 had the phrase: "The Motive Power of Heat," in it, whereas, Clausius believed that: "... there is no doubt that interior forces, exerted by the molecules ...." (From his 6th memoir on the subject.) Thus, in Carnot's mind, as soon as the ether known as caloric flowed out, the particles "returned" to exactly their original state. Whereas, we know, it is the movement of the particles themselves that transfer heat fromm a hotter to a colder region - giving the mistaken impression that there is "heat" liquid moving through the substance, or region. The difference is subtle - but fundamental. Carnot, then makes another mistake by calling this unfounded and untested view, "a fact" - perhaps, because it was widely held. A fact that he admits "would overthrow the whole theory of heat to which it serves as a basis," if it were ever to be falsified. This belief was the central mistake Carnot made, and its logical consequence was his conviction that transformations were reversible!. Because he thought of heat as a substance, he imagined the energy of the system as a whole was tied up in the heat itself! Therefore, if you remove the heat, you remove the behaviour. He firmly believed in Lavoisier's assertion, that it was the heat that pushed particles (atoms) apart, hence if the heat flowed out, then, the system and the particles that constitute it would "[return] to precisely its [- and their -] original state." Take careful note of the completely opposite view that Rudolf Clausius held, in his understanding of what heat was, and on why this would have profound effects on the behaviour of matter:

In the cases first mentioned, the arrangements of the molecules is altered. Since, even which a body remains in the same state of aggregation, its molecules do not retain fixed in varying position, but are constantly in a state of more of less extended motion, we may, when speaking of the arrangement of the molecules at any particular time, understand either the arrangement which would result from the molecules being fixed in the actual position they occupy at the instant in question, or we may suppose such an arrangement that each molecule occupies its mean position. Now the effect of heat always tends to loosen the connection between the molecules, and so to increase their mean distances from one another. In order to be able to represent this mathematically, we will express the degree in which the molecules of a body are separated from each other, by introducing a new magnitude, which we will call the disgregation of the body, and by help of which we can define the effect of heat as simply tending to increase the disgregation. The way in which a definite measure of this magnitude can be arrived at will appear from the sequel" Rudolf Clausius

You will note immediately, that in Clausius' explanation, the magnitude he calls disgregation - a word that has fallen out of use, but which we will re-establish - is a property of the molecules, not of the heat. This is where the confusion lies. When Lavoisier said: heat pushes atoms apart, he was erroneously assigning properties that belong to atoms and molecules, to heat. Heat causes disgregation by transferring energy to subatomic particles, but the dynamic of disgregation belongs to the subatomic particles, be they molecules or atoms. This is clear when we understand the movement of heated subatomic particles: they display an increased range of motion around a central position. If this dynamic was caused by heat, it would mean was pushing and pulling the molecules. This is obviously not the case, hence disgregation is a property of the molecule, not of heat. Disgregation, is of course, just the opposite of aggregation. If aggregation is bringing particles together, then disgregation is merely the opposite: to "loosen the connection[s]" that hold atoms and molecules together. The effect of heat in an element or substance is to "increase the disgregation." This is exactly what has been confirmed by all experimental data. If we take matter in its most aggregated form: the solid phase, and add heat to it, it will disgregate, by loosening the connecting bonds between atoms or molecules, eventually turning into its liquid and then gaseous phases for most elements; notable exceptions follow. Some substances, like 'dry ice,' leap frog the liquid state, and go directly from solid to gas. Others, like water, buck the trend of heat always causing an increase in disgregation. Clausius noted as much, writing about both the contrary nature of water in this regard, and the range through which the exception occurs:

If we take, for example, the melting of ice, there is no doubt that interior forces, exerted by the molecules upon each other, are overcome, and accordingly increase of disgregation takes place; nevertheless the centres of gravity of the molecules are on the average not so far removed from each other in the liquid water as they were in the ice, for the water is the more dense of the two. Again, the peculiar behaviour of water in contracting when heated above 00C, and only beginning to expand when its temperature exceeds 40, shows that likewise in liquid water, in the neighbourhood of its melting-point, increase of disgregation is not accompanied by increase of the mean distances of its molecules" Rudolf Clausius

But Clausius, had even more in store for us. Astonishingly, his understanding of the inner workings of elemental chemistry went further still. His unerring methodology being established on the facts, and the consequences of following such facts, to their logical conclusions. He explains what we today call degrees of separation, by explaining that each time sufficient heat is applied to an element, the:

... interior forces, exerted by the molecules upon each other, are overcomeRudolf Clausius

That statement is hugely significant, as it defines the underpinnings of what has become one of two ways to understand entropy. The other treatment of entropy was created by Boltzmann and Max Planck, and is based on statistical analysis. Understanding the difference between the two methods is critical to understanding why in the end, one is vastly superior to the other. For now we merely state their respective formulas, and thereafter delve into the meaning behind the theories, and hence their fundamental difference.

fdQ/T = N vs S = k log W

Here we must recall Caltech professor David Goodstein's words* (Episode 47: Entropy - The Mechanical Universe From 13:46 - 14:32):

Within Carnot's reasoning, Clausius and Thompson saw an amazing fact, and they saw in terms of an astonishing mathematical simplicity. In Carnot's ideal heat engine, the ratio of the heat taken in, to the heat wasted: was the same as the ratio of the two absolute temperatures needed to drive the engine. In other words, and this was the ideal that stemmed from Carnot's imagination: something that goes in, is the same when it comes out. If it's not the heat, and if it's not the temperature: what is it? It's the heat divided by the temperature at which it flows. And, according to Clausius that's entropy" Professor David Goodstein

But that is not true. Entropy was a not a concept Carnot was even familiar with, since the basis for his heat engine - the Carnot cycle - was dependent on the processes being reversible. He states on page 19 of his paper: "All the operations described above can be carried out in a direct and in a reverse order." And later in the same paragraph he reiterates the point: "A series of reverse operations to those above described could evidently be carried out...." In contrast, 'entropy' is the mathematical proof that reversible processes do not occur in nature! The processes cannot be reversed because the heat lost in running them forward, cannot be regained in order to run them backwards. Such loss of heat can never be reconstituted into its original form by physical means. This is not what Carnot believed, for he imagined heat to be a material substance, caloric that was conserved according to the conservation laws of matter, and thus was always available in its original form, allowing for continuous forwards and backwards (reverse) processes: the Carnot cycle! Notice how Wikipedia makes the same point:

In 1854 to 1862, Rudolf Clausius, building on William Thomson (May 1854) and Sadi Carnot (1824), formulated the characteristic functions, of what he was then calling the “second main principle” in the mechanical theory of heat, as a way to upgrade the Carnot cycle model, wherein heat, then defined as caloric particles, was defined as being conserved. In the new model, instead of heat being conserved, at the end of each cycle, there was now a new value of "uncompensated transformation," symbol N, that accounted for the "irreversible" nature of heat-transforming-into-work, aka positive transformations, and work-transforming-into-heat, aka negative transformations, and the end of one heat engine work cycle. The value of this N, at the end of all the cycles, is what Clausius eventually called "entropy increase"" Second Law of Thermodynamics - Wikipedia

Note the exactly opposite belief of Carnot below. I have marked the relevant phrases in bold, in each set of quotes, for ease of comparison. In the Wikipedia article explaining the Clausius term: "disgregation," we find the following summary from Wikipedia, which includes the Carnot quote of interest:

In 1824, French physicist Sadi Carnot assumed that heat, like a substance, cannot be diminished in quantity and that it cannot increase. Specifically, he states that in a complete engine cycle ‘that when a body has experienced any changes, and when after a certain number of transformations it returns to precisely its original state, that is, to that state considered in respect to density, to temperature, to mode of aggregation, let us suppose, I say that this body is found to contain the same quantity of heat that it contained at first, or else that the quantities of heat absorbed or set free in these different transformations are exactly compensated.’ Furthermore, he states that ‘this fact has never been called into question’ and ‘to deny this would overthrow the whole theory of heat to which it serves as a basis.’ the end of all the cycles, is what Clausius eventually called "entropy increase"" Disgregation - Wikipedia

Wikipedia then concludes with the following:

This famous sentence ... marks the start of thermodynamics and signals the slow transition from the older caloric theory to the newer kinetic theory, in which heat is a type of energy in transit.... In 1862, Clausius defined what is now known as entropy or the energetic effects related to irreversibility as the “equivalence-values of transformations” in a thermodynamic cycle. Clausius then signifies the difference between “reversible” (ideal) and “irreversible” (real) processes" Disgregation - Wikipedia

What is most important to note is the significance of the meaning behind the terms 'reversible' and 'irreversible.' Reversible means ideal, while irreversible means reality. Another word for 'ideal' is imaginary. Put another way, reality is based on irreversible, and not imaginary processes. I have included Clausius formula for N below, as a reminder of its definition.

N = fdQ/T

If Carnot had understood, or known of entropy, there would have been no need for Clausius to state that his theorem was "incomplete." The difference between Carnot and Clausius, was that the former believed heat to be conserved during thermodynamic processes, and it was this conservation of heat that allowed for reversibility; whilst the latter understood that heat underwent uncompensated transformations, in the course of its transfers: whether from work-to-heat; from heat to work, or from an initial temperature to a final temperature. These "uncompensated transformations," are what make the processes they are a part of irreversible! Since, they are "uncompensated," they cannot be recovered - they are lost! If they are lost, the process they were a part of, cannot be reversed to its original condition. This is clear! It's like when a relative of a murder victim, gets justice once the perpetrator is sent to jail. What do we always hear the relatives say: "I'm glad we got justice, but it won't bring So-and-so back!" Why? Because death is an "uncompensated transformation." Is there anyone reading this that doesn't understand that?

As for Thomson (Lord Kelvin), he did make great strides in trying to understand the fundamental reality behind entropy, but fell far short of the clarity achieved by Clausius. The stark truth is, as brilliant as he was, he never quite grasped the forcefulness of Clausius' insights. It took many years of him quarreling with and criticizing Clauisius, before he came to understand that Clausius was, in fact, correct. Note his take on the quality of Clausius' thinking: "The memoir of Clausius contains the most satisfactory and nearly complete working out of the theory of motive power of heat, but his hypothesis is so mixed, that the general effect is lost," and compare it with the assessment of another great mind Max Planck, who upon discovering the works of Clausius wrote: "One day, I happened to come across the treatises of Rudolf Clausius, whose lucid [clearly expressed; easily understood] style and enlightening clarity of reasoning made an enormous impression on me.... I appreciated especially, his exact formulation of the two laws of thermodynamics." In 1852, Thomson published: On a Universal Tendency in Nature to the Dissipation of Mechanical Energy. In this paper he showed a distinct awareness of the dynamics of heat dissipation, that is, that work can be completely converted into heat, but heat cannot be totally converted into work, because a certain amount of heat must always be lost to the environment (heat dissipation). This work showed an acute understanding for the effect of entropy, but not for the definition of its essence. In his own words:

The object of the present communication is to call attention to the remarkable consequences which follow from Carnot's proposition, that there is an absolute waste of mechanical energy available to man when heat is allowed to pass from one body to another at a lower temperature, by any means not fulfilling his criterion of a "perfect thermo-dynamic engine," .... As it is most certain that Creative Power alone can either call into existence or annihilate mechanical energy, the "waste" referred to cannot be annihilation, but must be some transformation of energy" Lord Kelvin

Recall that, without heat being transferred from a hotter body to a colder body, no work can take place. Furthermore: "The only way to use energy is to transform energy from one form to another."* (Law of Conservation of Energy - ENERGY EDUCATION) Those two statements taken together are the essence of a clear understanding of thermodynamics. Whenever, heat transfers, one or both of these conditions must be met. A decade after the aforementioned quote, on March 5, 1862, Thomson restated his views* (On the Age of the Sun's Heat), but again, he was merely identifying the effects of entropy, and not its truest nature, writing:

The second great law of thermodynamics involves a certain principle of irreversible action in Nature. It is thus shown that, although mechanical energy is indestructible, there is a universal tendency to its dissipation. which produces gradual augmentation and diffusion of heat, cessation of motion, and exhaustion of potential energy through the material universe. The result would inevitably be a state of universal rest and death, if the universe were finite and left to obey the existing laws" Lord Kelvin

As Kathy Joseph narrates in her video on Boltzmann's entropy equation* (Boltzmann's Entropy Equation: A History from Clausius to Planck - From 1:03 to 1:26): ""

I would like to start with the origin of the idea of entropy. In 1854, a German scientist named Rudolf Clausius noted that absorbing less heat at lower temperature was equivalent to absorbing more heat at higher temperature. Therefore, he called the heat over the temperature the equivalence value, and he would later call the equivalence value the entropy!" Kathy Joseph

Harkening back to Professor Goodstein's statement made seven quotes ago, we realize that the identification of this key ratio: Q/T, is the turning point in the identification of entropy as thee fundamental law of thermodynamics! and that identification belongs to Clausius, and only Clausius. It was Clausius who first noted the critical relationship between the ratios of heat and temperature, in 1854. It was Clausius who created the mathematical formula for entropy (which he called "equivalence values" at the time), in the same paper of 1854. It was Clausius who explained why loss of heat to the environment was an irreversible process. It was Clausius who figured out that if Carnot's reversible and irreversible transformations actually occurred in real life, there would be mechanism that would allow you to switch from one direction, to another: an equivalence value; and that since that equivalence value only had positive values, that meant the processes represented by negative equivalence values did not exist! I.e. reversible processes do not occur in nature. From these deductions, Clausius stated the second law of thermodynamics as: "The entropy of the universe tends to a maximum." The current expression of that same principle is: The entropy of the universe can only increase. Since, reversible processes must have an entropy of zero, and the entropy of the universe can only increase, it becomes plain to see that, reversible processes never occur spontaneously in nature. It was Clausius who in 1865 renamed the reality of "equivalence values," by coining the term: Entropy. It was Clausius who most succinctly defined the mechanics of entropy, and showed how it was connected to the "first fundamental theorem:" the mechanical equivalence of heat. He wrote in 1865: "The whole mechanical heat theory rests on two main theses: the equivalence of heat and work, and the equivalence of the transformations [entropy]." Rudolf Julius Emanuel Clausius was a genius!

Understanding entropy is more fundamental to understanding reality and thus nature, than is grasping the constitution and character of 'energy,' its sister reality. How important is entropy? In a statement of extreme hyperbole, famous British astronomer, physicist and mathematician Sir Arthur Eddington, compares it to Maxwell's equations and experimental observation, itself, two tenets of the scientific enterprise, to show that entropy would hold, even if the such pillars of science were to fail:

If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations - then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation - well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation" Sir Arthur Eddington

Despite these achievements, and perfect record in enumerating the varied and intricate features of thermodynamics, Clausius' work was to be attacked and its significance downgraded. In a chain of events that started favourably with Frederick Guthrie, proceeded antagonistically to Maxwell, progressed derisively to Boltzmann and culminated debasingly with Planck, within a few short years - an interval spanning from February of 1859 to 1900 - Clausius' great triumph of counter-intuitive thinking and logic, as based wholly on the vaunted scientific method, would be overturned and superseded by a hypothesis that was not fit to untie the laces of its predecessors sandals, never-mind fill its shoes. How did such a mockery of science get its legs? The mysteries of the inner workings of Scientism. Nevertheless, 1900 was the year Planck published a paper

For six years, I had struggled with the blackbody theory. I knew the problem was fundamental, and I knew the answer. I had to find a theoretical explanation at any cost - except the inviolability of the two laws of thermodynamics" Max Planck | Boltzmann's Entropy Equation: A History from Clausius to Planck (14:52-15:06)

The effect of Planck using Boltzmann's statistical methodology and formulating an equation for it, was that the great efforts of Clausius were demoted from a law of thermodynamics to being seen as a rough, and not totally accurate estimate of reality. Planck who had gotten his PhD on the second law of thermodynamics should have known better. However this would not be the last time Planck was less than precise in exercising his scientific powers - much to his discredit. In this instance, he had gone from:

The second law must either be founded on our actual experience in dealing with real bodies of sensible magnitude, or else deduced from the molecular theory of these bodies, on the hypothesis that the behaviour of bodies consisting of millions of molecules may be deduced from the theory of the encounters of pairs of molecules, by supposing the relative frequency of different kinds of encounters to be distributed according to the laws of probability. The truth of the second law is therefore a statistical, not a mathematical, truth, for it depends on the fact that the bodies we deal with consist of millions of molecules, and that we never can get hold of single molecules" James Clerk Maxwell

He inturn, influenced Boltzmann, who having read Maxwell extensively and having earned his PhD in the dynamical theory of gases, also promoted the narrow view that, gases - due to their immense number of fast moving, constituent particles - could only really be understood by studying their "average values." He wrote:

For the molecules of the body are indeed so numerous, and their motion is so rapid, that we can perceive nothing more than the average values. Hence, the problems of the mechanical theory of heat are also problems of probability theory" Ludwig Boltzmann | Boltzmann's Entropy Equation: A History from Clausius to Planck (@8:05)