What is Heat?

Energy

On the backdrop of Lavoisier's mistaken position that heat was an invisible fluid ether called "caloric," many scientists in the early 1800s were trying to figure out and verify the actual inner workings of heat. Normally, the relationship between science and technology is that a new scientific discovery emerges, and in time, it is harnessed to create technologies that are based on it. For this reason, the very word technology is a synonym for applied science. That term, "applied science," should make it clear that the relationship is causal and which of the two components, the science or the application of it in creating new technology - comes first. While that is true the vast, vast majority of times, in the case of steam engines and the industrial revolution they

spawned, the cart came before the horse. This is quite possibly because steam was such a simple resource to adapt in creating the rudimentary steam engines of the day that industry led scientific innovation.

Whatever the case, this was the scene in the early 1800s and scientists playing catch-up soon started trying to improve the efficiency of steam engines to maximize the benefits of the new technology. To do so, they would have to discover and harness the laws of thermodynamics. However, this task was made more difficult by their erroneous beliefs in caloric theory. The history of thermodynamics was shaped by many different scientists, instead of being masterminded, by just a handful - or one, or two as is often the case. Thus, since many contributors had a hand in crafting the final laws of thermodynamics, you can expect that no single scientist had a clear understanding of the thermodynamic landscape as a whole. Not until the genius of Rudolf Clausius, of whom

much more about later.

For now, we will continue our journey into the history of the fundamental discoveries of science by coming to understand what key components constitute the science of thermodynamics and briefly delving into how each was discovered and established. As with most things after Newton's turn on the scientific stage of accomplishments, the story starts with his point of view on a contested subject.

Understanding Energy, Heat, Work & the Four Laws of Thermodynamics

Thermodynamics, is the area of physics which rules every other scientific discipline, whether chemistry, biology, metallurgy, structural engineering, rocket science or any other you would care to name. Thermo means heat, and dynamics refers to movement. A critical point to understand is that unless there is a difference in temperature, heat cannot be used to perform work, as it will not transfer from one object to another. For heat to transfer, there must be a temperature gradient. That is, one object or area must be hotter than another, for heat to be converted into work! Thus, it was this crucial understanding of what heat was, and how and why it transferred from one object to another, that would prove pivotal,

to understanding the universe and defining the hard boundaries of all other scientific disciplines!

Thermodynamics is described by Hank Green of CrashCourse as: "the physics of heat, temperature, energy and work." Incredibly, at the beginning of the 19th century, that is, at the beginning of the 1800s, scientists misunderstood all four of those fundamental concepts! They didn't understand heat, as they believed in caloric. They hadn't defined what the entity we call temperature was. They also had no concept of the terms energy and work, which are so familiar to us, we take it for granted that mankind has always recognized their existence and more importantly, their significance. In fact the term "energy," was first used in its technical scientific meaning

only in a 1807 lecture given by Thomas Young, who had earned fame after his groundbreaking double slit experiment that proved that light acts like a wave. And its first recorded use in the English language was not long before, in 1783, when it was used to communicate a sense of "dynamic energy" (Mirriam-Webster online dictionary). The truth about how recently we figured everyting out is somewhat shocking. Up until roughly 200 years ago, no one had managed to work out the scientific breakthroughs that led to the discovery of these foundational scientific truths and their universal application on all physical systems. To get to the bottom of this matter we will go through how all four of the principles of a thermodynamic system work, and the brief history of how they

were each discovered. Incidentally, thermodynamics has four key variables: temperature; energy; heat; and work. And four laws that define how those variables work, classified as the: zeroth law; the first law; the second law; and the third law of thermodynamics. I will explain later why the naming convention is so unusual. We start with Energy, and the journey to its discovery and experimental verification. We will do the same for each of the other three main variables in thermodynamics and end of with an introduction to yet another important aspect of all such systems: the surprising existence of - Entropy.

Newton VS Leibniz

Newton, who, of course had come up with the laws of motion, had tried to quantify the force with which an object with mass would impact any other object it would come across. The best he came up with was that the impact that such an object would have on other objects would be the product of its mass multiplied by its velocity. Let's describe that as: f = M x V. In this, he and noted French mathematician Rene Descartes agreed. However, consensus is not verification. In another camp was German polymath and renowned genius Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz. He believed that the force of impact could be calculated by mass multiplied by the velocity squared! That is, f = M x V x V, or simply f = MV2.

To get the flavour of the difference between the two formulas, we need only consider the following scenario. If you dropped a ball from a certain height, into say some soft clay, it would sink to a certain depth. But what would happen if you increased its height above the clay by a factor of two? Newton's formula says the result would be the ball traveling twice as far into the soft clay. Leibniz disagreed, saying it would travel four times as far! Since 2 (from twice the distance) multiplied by 2 (the effect of squaring is to multiply something by itself twice) is four. Who was right?

Into the picture came someone who would meld the correct conclusions from both men and come up with a refined understanding of such a force. Incidentally, in Newton's formulation of this equation, people had observed that whenever two objects with equal mass and velocity collided, they were bound to stick to each other, so Newton's formula came to be called the "dead force." While Leibniz' formula came to be called the "living force." With that we delve deeper into which of the two claimed forces was the correct understanding of nature with our next great scientist - Emilie du Chatelet.

Emilie du Chatelet

Understanding & Refining the Living Force

Emilie du Chatelet (17 December 1706 - 10 September 1749), was truly a bright spark. Born of a wealthy family and trained as a mathematician, she had the gift to think outside the box and bring disparate ideas together. Nowhere would that distinct ability be needed more than in helping to resolve the raging debate of her day: what was the nature of heat? A mind as sharp as du Chatelet's was a critical contributer to the eventual resolution of the task at hand, because beneath this seemingly simple challenge lay a hornet's nest of complexity. As Kathy Joseph notes Du Chatelet lived in times of fervernt nationalism, where many in society backed a theory - not on its merits - but, merely because the person who proposed it was from their own nation. Assessing scientific

discourse on the veracity of its facts, or the logic on which such theories were based came second to nationalistic pride. Emilie du Chatelet was different. A free thinker who valued ideas on their merit and for their explanatory power, she relied on experimental results to establish, which of the many contemporaneous philosophies would lead to true scientific knowledge. But she wasn't just a commentator on scientific discourse, she was a most notable contributor to the growing catalogue of scientific knowledge.

The Problem with Scientists Depending on Ethers

We come upon her at a critical juncture in the history of science. Much had been learned about the true nature of reality, but much more was yet to be gleaned, and it would require minds with a perchant for sticking to the data to uncover what yet lay beneath the shroud of ignorance. Her contributions come as we have moved from the four ancient elements of the early Greek thinkers, past the ether of terra pingus, which in turn, morphed into the ether of phlogiston. The point about all those ethers, is that they were trying to explain fire or combustion, among other chemical processes like respiration and oxidation (rust). With Lavoisier's insights into the true nature of chemical compounds and elements, humanity had gotten a foothold on the beginnings

of the periodic table and the science of chemistry. We now faced different challenges! Mankind had to understand what the true nature of the phenomenon called "heat" was. And how it worked? In tackling this problem, Lavoisier had dissapointly regressed back to invoking yet another ether! Do we never learn? This time the ether was in the guise of Caloric - and as with all ethers, it was: invisible, colourless, odourless, and hard to detect. Ethers are also usually described as self-repellent. This property is usually used to describe some dynamic of how they are supposed to work. In this instance, the caloric ether was described as a fluid (hence its supposed ability to flow from one substance to another, or from region of a body or entity

to another). Since it itself was supposed to be heat, as it flowed it was said to carry heat in and out of different substances by "flowing" from hotter to colder bodies. As you are surely taking note: sometimes ethers are described as "fluids," as is the case with caloric. Other times they are described as invisible "crystals," as was the case with Aristotle's heavenly spheres; and at yet other times they are described as a type of "air," as was the case with Becher, Stahl and Priestly and their beloved phlogiston. A pattern that I am sure you have noticed.

The standard description of ethers as being colourless, odourless, hard to detect etc. make them vedry appealing to philosophers when they formulate theories on subjects for which no data has yet been collected. Since their ideas are meant only to match how things appear - and not how they actually function, all that is needed is a blank - and importanly - hard to detect canvass onto which the suddenly sage philosopher can unleash his full imagination about the underpinnings of how this or that phenomena in nature actually works. And, "voila!" An instant and detailed understanding of nature springs into existence! This is the sci-fi fantasy of ethers.

By definition - because they are so cleverly constructed - it is near impossible to prove that such ethers are false without data. Only with empirical data and the advent of the right working model that then makes sense of the experimental data and verified observations are such ethers ever debunked. Ethers are fake science. Their role is to make the general public think they understand how this or that phenomenon in nature works. They accomplish this without data or empirical evidence because they only have to map to how things LOOK, not how they actually function. They are thus, initially very convincing, and easily become conventional wisdom. Sometimes, as in the case of Aristotle's ether-based theories, for well over a thousand years

of human history! You will note, also, that ethers are only invoked at the beginning of an enquiry into an unknown, or currently misunderstood part of nature. They are only ever used before exprimental evidence is collected and catalogued - never after. They are never invoked after how something works has been been proven through the scientific method. In other words, no scientific discovery has ever been published with experimental evidence AND an ether-based explanation. When Lavoisier invoked an ether after he already had used experimental evidence to prove the existence of oxygen, the ether was not invoked to explain oxygen - but heat! A yet, misunderstood phenomenon of nature.

Here is Hank Green of YouTube's Crash Course channel explaining the invocation of ethers in the 1800s. Pay close attention to his words, and take note of what conditions such ethers

were invoked under:

[Lavoisier] used the caloric theory, which explained heat transfer as an ether, or colourless fluid, that migrated from a body at a higher temperature to one at a lower temperature. This made sense to Lavoisier when he was upending chemistry. But it was wrong!

Infact, ether was the explanation for many unkown phenomenon in the eighteenth century. And there were a lot of ether theories

Hank Green: Thermodynamics #26

Understanding Why Scientists Resort to Ethers - & Why they Never Work

"For many unknown phenomenon," Green said. That is, while nothing much is known about a particular subject. That is the historical scientific record of when ethers are used! It requires pause to realize the gravity of what Green just explained. First we realize how ethers are always used: as a broad brush to try and explain something before any empirical evidence opens up the possibility of a fact based understanding - and explanation. Second: this practice of using an invisible broad brush to gloss over the absence of facts and actual observational data is utilized again and again to explain all manner of misunderstood phenomenon. It doesn't matter what field the unknown phenomenon is in, ethers are

routinely applied to try and explain different mysteries of nature: from the cosmos in space, to how atoms function in chemistry. It's simply astounding. As Green says: "... ether was the explanation for many unknown phenomenon in the eighteenth century. And there were a lot of ether theories." The point is clear. Ethers are routinely used as a universal bandaid for trying to explain the unknown - as long as there is no data. It's as if errant scientists ask themselves, "Are there any new phenomena to be studied? Well ... instead of wasting our time and effort trying to figure them out, why don't we just use our imagination and an ether to explain them?" That alarming attitude is exactly what scientists have embraced time and time again throughout the history of

science. Also, ethers are readily adopted by the general public because they seemingly confirm their own everyday assumptions about a misunderstood phenomenon, and so gain quick acceptance. Consider, which was easier for the common man to accept in ancient times: the then preposterous claim that the earth moved - and revolved around the sun while spinning on its own axis every 24 hours; or the seemingly obvious claim that the sun revolves around the earth daily? "Duh. That's why we call it "sun-rise" and "sun-set," and not earthrise and earthset...." Lol. Just one thing: the truth was the exact opposite of expectations based on casual, data-less observations predicted! In the

end, ethers never result in useful science.

Emilie du Chatelet was no etherist. It was quite obvious to her, having studied the works of Newton in great depth, including his most profound volume Principia, that he was right about the laws of motion. But being right often doesn't mean always right. Having an open mind she questioned who was right between Newton and Leibniz as to the equation of the force with which an object would impact another. She ran her own tests and discovered that Leibniz was correct. The living force was the more accurate formula for understanding the dynamics of objects.

But there is no force in current physics that is known as the living force. So, we now trace how science developed from the living force to our common term - Energy.

From Caloric to the Founding of the Laws of Thermodynamics

It should not surprise you that the reason Emilie du Chatelet takes a starring role at this point in our story is because, where the brilliant Lavoisier failed - she excelled. Again, the factor that was holding progress back was using the wrong model. Using ethers. We have set the stage as to Newton's dead force formulation and the living force as proposed - and experimentally proven - by Leibniz. Emelie, as ever reliant on experimental proof and observational evidence, agreed with Leibniz and said the living force calculated for colliding objects (so named because the objects mostly continued in motion after impact) was indeed determined by the equation f = M x V2. We are now at the point of having established

a formula for a quantity that - in our story - we currently call the "living force." Keep in mind that as we journey through the many and varied independent discoveries of thermodynamics, we are going to come across what the inventors initially called these properties or entities, and yet later come across what the scientists who refined and added to their work called them, and only lastly arrive at the familiar terms we use to define said properties and entities today. A second caution is necessary to appreciate that nature has many interacting dynamics. Sometimes many things that are thought of as being different prove only to be different manifestations of the same deeper reality, as is the case with the electromagnetic spectrum (light). Other times, what we might

initially think of as one indivisible thing proves to be made up of multiple smaller components, as was the case with atoms. Let us continue.

To show how science builds on successive victories of human understanding and as a testament to du Chatelet's impressive genius I provide the following anecdote about how she used the recently verified equation of the living force in determining a key variable about the nature of light. Du Chatelet, went against the grain of the conventional wisdom of the time and opposed her contemporaries, by insisting that light cannot have mass. A then, very heterodox idea. Her reasoning was clear, flawless, precise and most importantly - correct. If light were not massless, she argued, then according to the formula for the living force, light would thus having an immense resulting force due to its tremendous speed - and the fact that it was squared. In such a case, she wrote: "a

single instant of light would destroy all the universe." The reasoning could not be faulted. And light, as we now know, is indeed massless. This conclusion was written in a publication that outlined her fact based theory of how light and fire worked. And it gives us insight into how she got involved in the discoveries which led to how heat works. A hundred years before others realised it, du Chatelet concluded the following about the nature of fire (heat) and motion:

Thus, far from motion being the cause of fire, as some philosophers thought, fire is on the contrary the cause of the internal motion of the particles of all bodies

"

Emilie du Chatelet

This was more than a 100 years before the brilliant Lord Kelvin would arrive at the same conclusion in 1848! Her reasoning was a clear rebuttal of phlogiston theory which imagined combustion to be the transfer of phlogiston out of a substance. It was this level of insightful thought that she brought to the debate about the nature of heat. Although she died in 1747, her scientific thinking helped shape the 1800s and the paradigm shift necessary to move scientists from thinking of caloric as heat, to correctly formulating the laws of thermodynamics as the proper model for heat and its effects. Du Chatelet's core genius lay as Kathy Joseph puts it, in her taking: "What seemed like disparate and opposing ideas, and elegantly mesh[ing] them together."

Thomas Young

From Living Force to Energy

As we mentioned earlier, the term energy has not been in use in science for as long as you might think. It was first used by Thomas Young in one of a series of lectures that he was giving about the living force. He found it much more expressive of he idea of a living force, because it was defined as "dynamic energy." Thus, through Emilie du Chatelet, mankind went from Newton's incomplete idea of the dead force, to the more correct formulation proposed by Leibniz of a living force. This living force, was synthesized by du Chatelet into the rest of Newton's ideas and calculations about how the universe actually worked. Sixty years after her death Thomas Young renames the living force: energy - the name it still

has today. But there would be more refinements, for the concept of energy was only just getting off the ground. Much more was needed to be discovered before mankind would get an accurate picture of how the universe works. For one thing, we needed to empirically establish the relationship between energy and work. We needed engineering insights.

Understanding WORK: A Crirical Refinement to the Energy

About a hundred years after her death, we are now nearing the mid-1800s and the great debate about the nature of the living force - or energy - is still unsettled. These things sometimes take time. After her death du Chatelet's scientific reasons were captured in the French encyclopedia by Denis Diderot one of its co-authors. Even with that foundation, not much progress was made in further defining energy. That was until a former military engineer left the armed forces to become a full time scientist. His former employment gave him a practical edge in engineering that most scientists do not possess. His name was Gasbard-Gustave de Coriolis.

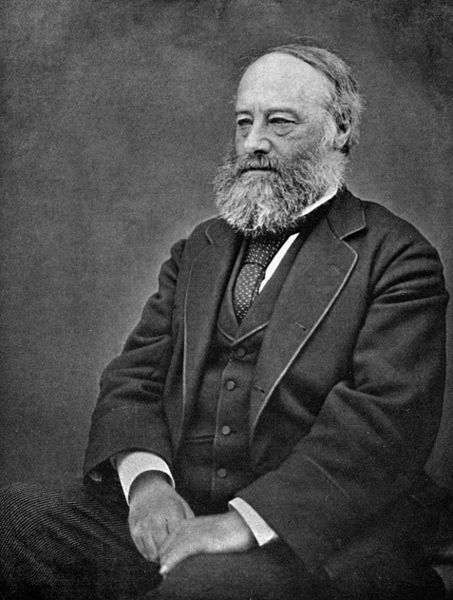

Gasbard-Gustave de Coriolis

Coriolis (21 May 1792 - 19 September 1843) increased human knowledge in various ways. It was Coriolis, who in his experiments with forces, masses and movement refined the world's understanding about the nature of the "living force." His initial foray into this field was a paper he published in 1829 about the results of some of his experiments. In it he created a new scientific term called "Work." He stated, "The definition of work is ... the product of the space tranversed multiplied by a force directed perpendicularly to this space." But that wasn't the groundbreaking part. Quoting Kathy Joseph, he further found, "... that if an object was pushed on a flat surface, then [that] object would have a change in one half the mass times speed squared." Through these

experiments Coriolis had managed to refine the equation for the living force into the form we still use today! The equation for the living force is thus f = 1/2mv2. But Coriolis' penchant for experimentation had gone even further. He played around with his machinery and found that if a machine did work by pushing something uphill, then the calculation for the amount of living force necessary was different. Again Joseph expresses it clearly: "The work minus the weight times the height equaled the change in living force." Let us write that out so we can clearly see what is happening. We will then isolate the work variable on the left hand side of the equation so we can see how the other variables result in the

amount of work done. Our aim is to understand what the equation means. Though he established this formula using calculus, I will write it out below in simple mathematical terms for clarity and ease of understanding. It is very straightforward:

W - ph = 1/2 MV2 - 1/2 MV02

Where W is work, p is weight (we can't use 'w' as a symbol because we have already used 'W' for work), h is height, M is mass, V is the initial velocity, and V0 is the final velocity. To really understand what this equation is telling us, we must isolate the work variable, resulting in:

W = 1/2 MV2 - 1/2 MV02 + ph

We will remember from grade school that in an equation whenever we take a term across the equal sign we must change its sign. Thus, - ph turns into + ph, again where ph means the weight times the height of the object in question. In this form what the equation is telling us becomes very clear. When a machine pushes an object up a hill the work needed to do so requires TWO TYPES of forces - not one!

It requires the difference in the living force, from the initial state to the final state plus another kind of force, which due to its definition (weight times height), you might recognize as gravitational potential energy. That's what we call it today. In a paper published in the 1852 William Thomson (Lord Kelvin to you and I), wrote about dividing the stores of mechanical energy: "... Into two classes - statical and dynamical." He went on to explain the difference between the two classes: "A quantity of weights at a height, ready to descend and do work when wanted, an electrified body, a quantity of fuel, contain stores of mechanical energy of the statical kind." On the other hand, he continued,

"Masses of matter in motion, a volume of space through which undulations of light or radiant heat are passing, a body having thermal motions among its particles ... contain stores of mechanical energy of the dynamical kind." Of course, you still don't recognize those terms, which tells us that further refinements were soon to come along. As sure as day follows night, in 1853 William Rankin renamed these types of energy potential and actual. We are getting warmer. It would take one more adjustment to get the two terms we use today. Wresting control of the coining of these terms back, in 1855 Thomson then accepted the term potential energy, but renamed actual into the term familiar to all of us today - kinetic. Thus, by 1855 makind had managed to go from the "living force"

of more than a century earlier to first energy, and then more accurately kinetic energy. We had also managed, through Coriolis, to understand the concept of work, and that work involved all the types of energies that could be called upon in any one situation. This necessitated the naming of work that invovled gravitational effects, and thus was born the term "potential energy." Into these two categories fall all the types of energy known to physics. Lord Kelvin listed some of them. Let me give a more complete catalogue:

Kinetic Energy

-

Mechanical

-

Thermal

-

Electrical

-

Radiant and

-

Sound

Potential Energy

-

Nuclear

-

Gravitational

-

Elastic and

-

Chemical

All energies are either active or stored. Kinetic or potential. Later on, a great scientist by the name of Hermann von Helmholtz will detail some of the other forms of energy for us.

Into our expanding knowledge of the foundations of thermodynamics we must now factor in heat. Just how exactly does heat relate to the science of thermodynamics?

Heat

Nicolas Sadi Carnot

The inquisitive nature of Sadi Carnot's (1 June 1796 - 24 August 1832) intelligence led him to try and come up with the most efficient heat engine imaginable. This endeavour he regarded as of the highest priority, as he thought it would prove critical in allowing France to become dominant in world affairs, remarking: "The study of engines is of the greatest interest, as their importance is enormous, and they seem destined to produce a great revolution in the civilized world." He thus pursued his quest, as a form of patriotism. It became clear to him that every heat engine had three components in common: a heat source (analogous to fuel), a heat sink (a second heat reservoir at a lower temperature), and a piston (the part doing the work).

The heat sink is critical to the working of the engine because it is its lower temperature that ensures heat transfer. Only when heat transfers from the hotter part of the engine to the cooler part of the engine, can some of it be used by the piston to do work. Let me repeat that because it is that important. If there is no difference in temperature between the two heat reservoirs, then heat CANNOT transfer and no work can be done. In fact, the greater the difference in heat between the hot and cold reservoirs in a heat engine, the greater its its efficiency. The greater the amount of work it can accomplish. The cold sink which allows for waste heat to be released into the surrounding environment is a prerequisite for heat

transfer, not a product of it. In all this Carnot was correct.

However, as his ideas on heat were wholly based on caloric theory, he carried some misconceptions. For instance, he used the term "flow." This was meant in exactly the same way we mean it when we say a river "flows." This misconception was because he thought heat was a literal 'fluid,' and of course, fluids flow. Even today most scientists still refer to heat "flowing" as a carry-over from the phlogiston and caloric theories. The other carry over is to the reference of "burning calories." Of course, the correct description of the dynamics of heat is to say it is "transferred," from hotter to cooler objects. Subsequently, as a strong believer in caloric theory, Carnot assumed that heat could neither be created nor destroyed, only made to flow spontaneously from a hotter region/object to a colder one. He mistakenly, believed that it was this flow of heat that performed work, and not its generation or consumption. This was the only

logical conclusion for believers of caloric theory, for if heat was a substance, then according to the law of the conservation of mass, it could neither be created nor destroyed. Resulting in the only way it could could generate work being it flowing from one area of an engine to another. He stated:

The production of motive power is then due in steam-engines not to an actual consumption of caloric, but to its transportation from a warm body to a cold body

Sadi Carnot

Carnot had worked diligently to formulate his ideas on ideal engines. He had established that two heat reservoirs are necessary to do work. In the meantime, convinced that caloric (heat) was indeed, a material substance, Carnot sought to confirm whether or not its dynamics were governed by the law of the conservation of mass. Knowing the answer to that would prove final in settling the matter, for we now know, and in the early 1800s they were quickly learning, that such laws dictate how all material substances behave. He published his initial thoughts on the subject in 1824. Being the stellar scientist that he was, his thought process and findings were incredibly close to the truth, with the exception of ideas he inherited from the caloric theory. Yet, his careful, scholarly nature

eventually guided him to the right conclusion - despite his key initial misguided assumption. This was to his great credit as many scientists are too proud to adapt their initial hypothesis, in the face of contrary evidence. We see that today, within the wholly science fantasy based string theory community. As for Carnot, he formulated his final understanding in a second manuscript, that would only be published 58 years after his death, writing:

Heat is simply motive power, or rather motion which has changed form. It is a movement among the particles of bodies. Wherever there is destruction of motive power

there is, at the same time, production of heat in quantity exactly proportional to the quantity of motive power destroyed. Reciprocally, wherever there is destruction

of heat, there is production of motive power

""

Sadi Carnot

That is what the scientific method in action looks like. That is the difference between forming an opinion on nature based on how things look, and forming an understanding based on observational data derived from experimental evidence! So noteworthy is Carnot's turnaround that it is worth deeper scrutiny. In his quote he is making FIVE important statements: 1) Work ("motive power") and heat are different forms of the same thing, i.e., you can change one into the other; 2) Heat is associated with the movement of atoms ("particles of bodies"); 3) Heat can be produced; 4) Heat can be destroyed, and finally; 5) He understood that the dynamic relationship between converting heat to work, or work to heat was exact, stating: "production of heat in quantity

exactly proportional to the quantity of motive power destroyed." (This statement also encompassed the reciprocal scenario.)

The importance of thoroughly understanding these truths cannot be overstated. As, if heat is a fluid, then it would create work by moving from hotter to colder regions, and the conservation law that would apply to it, is the one for 'matter,' meaning before and after work has been done, there will be the same amount of heat present, just in a different form - if necessary. But, if heat were a type of energy instead, then the conservation law that would apply is the one for "energy" which states that:

Energy can neither be created nor destroyed, only converted from one form or energy to another. This means that a system always has the same amount of energy, unless

it's added from the outside.... The only way to use energy is to transform energy from one form to another

"

https://energyeducation.ca/encyclopedia/Law_of_conservation_of_energy

That last sentence is the KEY that ties everything together! Put another way: energy cannot be used without it being converted from one form to another." In turn, for such a conversion to occur in a heat engine, there must be heat transfer. Heat must be able to move from a hotter region to a cooler one. Of course, work is itself a form of energy. So requiring a conversion means work cannot produce work. You need a source of fuel, in the form or heat (for a heat engine), and it is that heat that is turned into work. Making for two forms of energy being involved in the process. For instance, consider the correlation between kinetic and potential energy. An object held aloft, 10 meters above the ground has 100% potential energy (for an object of its mass at that height), and 0% kinetic energy - as it is motionless. But it can do work, when it is dropped. As it drops, according to the law of conservation of energy, the potential energy must be converted

to kinetic energy in such a way that the total of the two forms of energy must always equal 100%. That is, when the object starts descending and has generated 25% kinetic energy, it must correspondingly have 75% potential energy left. When it's near to hitting the ground and has moved 8.5 meters down, it will have generated 85% kinetic energy, then it will have, must have, 15% potential energy left. That is what conservation laws mean.

There are many ways of defining thermodynamic laws, each of which are valid. This applies to the definition of work, which fits more than one definition. Whilst work was defined by Coriolis as the product of an applied force moving an object a certain distance, it is also the conversion of one form of energy into another. This is why all industry needs to convert raw materials into a usable form of energy so that they can produce work. Your body is powered by food. Your car is powered by fuel. In both these scenarios, one form of energy is changed into another form of energy in order to do work. Think of a hydroelectric dam that uses water flow to generate electricity. In such a system the kinetic energy of large quantities of water turn a turbine, which

subsequently turns an electric generator. This process effectively turns the kinetic energy of moving water into electricity. As Dr Shinin Somara explains: "These conversions are important, becasue energy doesn't jsut come out of nowhere. It needs to come from some other type of energy. So, to better understand how energy can be converted, you need to understand thermodynamics." Indeed. In this scenario work is the conversion of one form of energy into another form for a beneficial purpose. As of now, we know some very useful information about work, but we still have not established and quantified the true nature of its relationship to heat! Dr. Shini descibes thermodynamics as:

The branch of physics and engineering that focuses on converting energy, often in the form of heat and work. It describes how thermal energy is converted to and from other forms of energy and also to work

""

Dr Shini Somara: The First & Zeroth Laws of Thermodynamics: Crash Course Engineering #9 (@1:18)

Establishing the Exact Relationship Between Heat & Work

It is the exact nature and quantities of this conversion that we would now like to concern ourselves with. Once we understand that, we will understand how many processes in nature work, and even more importantly - why! As a precursor to that discussion, though, let us now focus on the first real established proof that heat was not an ether. This was discovered by another military engineer - Count Rumford.

Count Rumford

Born Benjamin Thompson (March 26 1753 - August 21 1848), this American-born British physicist would distinguish himself at multiple points in his life. Once when he was knighted by King George III, and became Sir Benjamin Thompson, and later, in 1791 when he was given the title of Count Rumford after becoming a Count of the Holy Roman Empire. Count Rumford was a man of many talents mixed with some rogue characteristics. Focusing on his more amiable side, we list some of his notable faculties, which included a knack for design, being a capable inventor, and a stellar ability for administration. Of course, the reason we are interested in him is for his contributions to the then burgeoning science of thermodynamics. Having been exposed to

science at the age of fifteen, he developed a life-long love for scientific experimentation, honing his skills at it throughout his life. He attained wide acclaim from his experiments with gunpowder in 1781, and thereafter continued his scientific endeavours with investigations into the nature of heat, itself. He discovered a way to measure the specific heat of a solid substance. Specific heat "... is the amount of energy that must be added, in the form of heat, to one unit of mass of the substance in order to cause an increase of one unit in its temperature." (Wikipedia) As was often the case in Rumford's days, when many others were trying to solve the same problems, someone else had recently discovered the

method independently and published his results first. This is known as having scientific priority. Having just missed the mark of gaining more fame and prestige, Rumford remained undeterred, he soldiered on with his queries - to glorious effect.

His next discovery came from the opportunities his work - as a military man - gave him to carry out scientific experiments, and he used these opportunities to fullest effect. Thus it was, that Count Rumford was the one who managed to break the empirical stranglehold the caloric theory then held over the scientific world, by producing the first experimental evidence of its falsity. While all scientists under the sway of caloric theory held that heat was a fluid, an ether, Rumford showed empirically for the first time that heat could not be a fluid based ether that flowed from one substance into another, but rather, that heat is transferred from one substance to another dynamically, that is, it is transferred

through the motions of one object that is in thermal contact with another! But what does that mean?

His 1798 paper An Experimental Enquiry Concerning the Source of the Heat which is Excited by Friction proved definitive in establishing how heat transfer actually worked. Rumford used a drill to bore a hole (length-wise) into the center of a long solid piece of cylindrical metal. The whole left after such drilling would then serve as the barrel of a military cannon. Think of the after effect as hollowing out a metal straw. In fact the word cannon is taken from the Italian "canonne," which means "large tube." Since solid metals don't come with holes, their barrels have to be drilled. This was Rumford's work, and he used it to spectacular scientific effect, for he had more in mind than just creating military

hardware, he wanted to quantify how much heat was produced in this process. He thus submerged the metal in water and drilled the barrel underwater! When he did, he noticed that so much heat was created by the friction that after a couple of hours, the water began to boil. In fact, since he had already found a method for calculating the specific heat of solid objects, he decided he would go one step further. He compared the amount of heat generated in this slow process to the amount of metal he to begin with and determined that if the heat produced by friction from this process were to be used to heat the metal from which the cannon was made, all of the origianl metal would have melted. This made it clear that the heat could not have

been part of the of the cannon's metal beforehand: otherwise the metal would not have been in solid - but rather in molten - form. Thus, he decided, such heat was the result of some other function. This function he concluded was motion. In his experiment: heat was a function of the friction between the drill bit and the metal of the cannon he was grinding it with. What's more, repeated boring of the same piece of metal did not affect its capacity to create more heat. This meant caloric was not a conserved quantity! If it was, the metal's capacity to generate more heat would have decreased over time, since there would have been less and less caloric left

in the metal after each episode of drilling.

He further measured the specific heat of both the remaining unbored material, and the specific heat of the material that had been machined away. The result, as you may have guessed is that they were the exact same value - since they were made of the exact same material. This showed empirically that no physical change had taken place in the cannon's original metal. No caloric had been transferred out of it into the boiling of water as the caloric theory asserted would be the case. For according to the already proven and verified law of the conservation of mass, since some heat had obviously been transferred into the water to make it boil, if heat was a caloric ethe, that is a material substance, then the metal should have had less of that

caloric substance after boring than before the experiment began. In fact, it should have been less by the exact same amount as the heat that was transferred to the water: that is what conservation of mass means! Remember Lavoisier's pioneering work with sealed glass enclosures in that regard.

However, the results showed that the metal still had the exact same capacity for generating new heat as it had before the experiment was run. This simultaneously destroyed two claims of caloric theory: 1) Heat could not be a fluid ether called caloric as the amount of heat generated by drilling the cannon was more than what was required to melt its metal and change it from a solid to a liquid state, hence the mechanism of heat generation could not be a substance that was to be found in the metal itself. It had to come from somewhere else, from some other function: 1) The nearly inexaustible ability to generate heat proved that such heat was a product of friction not a liquid ether, and; 2) Since the metal shavings and the metal of the

cannon had the same specific heat, this proved that heat did not follow the law of conservation of mass as established by Lavoisier. Another requirement that heat would have to meet were it an invisible fluid. As such heat could not be a material substance. Otherwise, the law of conservation of mass would have ensured that as more and more caloric was transferred to the water, there would be less and less heat left in the metal to be transferred. For the two values must always equal 100%.

Rumford, therefore, correctly concluded that the dynamics of heat were incompatible with its descriptions according to caloric theory. Moreover, since the only other variable in the experiment that generated so much heat, was the motion of the boring tool he had used, he concluded that motion was what was responsible for the heat generated. In this case, that would be the motion of the boring tool against the metal of the cannon, meaning a very specific kind of motion - friction. As you might expect by now - if you have noticed the pattern that accompanies genuine discoveries - Rumford's explanation of heat was shunned by his contemporaries, as it thoroughly discredited the caloric theory they were so used to.

His new theory of heat would only the traction, recognition and status it deserved in the following century. As someone once quipped: "Science progresses one death at a time." These developments bring us to about the middle of the 1800s and a man who was obsessed with heat and its power to generate motion as examplified in steam engines. His name was Sadi Nicolas Carnot. But before we get to Carnot, let us have a brief review of the many terms and concepts we have covered thus far.

Review of ENERGY, WORK & HEAT

Below, we will review the different kinds of energy we have discovered so far. And as a companion to this section, I include the title of a very informative video on thermodynamics from the YouTube channel Crash Course. It's called: The First & Zeroth Laws of Thermodynamics: Crash Course Engineering #9. It gives definitions for work, heat, energy and a few other nuggets. It is well worth your viewing effort.

From Living Force to Energy

We went from dueling between the definitions of living and dead forces, realizing along the way that in this instance Leibniz was right and the living force carried the day. In time, Coriolis formulated a new equation and established a new entity: Work. He later used calculus and his new "work" formula to realize that the living force, i.e., the energy, needed to push objects mechanically on a flat surface was not mv2, but rather 1/2mv2, that is, half the mass multiplied by the velocity squared.

Through a series of refinements by other scientists, namely Lord Kelvin, William Rankin and again Lord Kelvin, the living force with its now complete formulation came to be called kinetic energy. Moreover, humanity came to understand that energy was only part of the equation for work. But, we are not done with Coriolis ...

A New Development: Defining Work More Accurately

Thereafter Coriolis, ever the military man, soldiered on to uncover a yet deeper level to the wonders of energy. After first, defining work as the product of the force applied upon an object and the resultant distance that object moves in the direction of the force. He continued doing more experimental work on the different types of work that could be done, in addition to the dynamic of pushing objects along flat surfaces, he also pushed them up hills, and uncovered an entirely new type of energy: gravitational potential energy. That is, the potential energy that objects can have dependent on their height above ground. The higher they are, the more potential energy they have. Thus, work now had two variables

that always had to be factored in to get an accurate value for how much work has been done: kinetic and potential energy. This refinement allowed humans to understand deeply the mechanics of many different processes and to engineer processes and machinery that could harness such forces efficiently. It is important to not the relationship between work and kinetic energy (the old "living force") and stored potential energy. These last two varitables are part of the forces that act on an object when work is done. Kinetic and potential energy are part of the equation for determining how much work was accomplished. And, yet, there was still more to uncover before mankind's knowledge of thermodynamics could be considered complete - heat!

SOMETHING MISSING: Nothing Physical Can Exist Without Heat

What was the missing factor? At present all we know is that heat is not an ether and that it can be generated by different functions including friction, as was the case with Count Rumford and his cannons. But, as of yet, we are still unsure of how heat ties in with work? In fact, we don't even yet know how heat relates to energy. So that is our present task. To find out what, if any, relationship exists between heat, work and energy? Back in the 1800s, it was obvious from steam engines that heat (in the form of steam) could be used to do work (by powering steam engines). But there was still much ground to cover in gaining a fuller understanding of this phenomenon. What was needed was a quantitave understanding of the relationship between heat and work. While Carnot

recognized the immense value of steam engines to industry, writing: "Already the steam-engine works our mines, impels our ships, excavates our ports and our rivers, forges iron, fashions wood, grinds grain, spins and weaves our cloths...." He also lamented the paltry knowledge humans had of the underlying scientific principles that guided its operations, commenting that, "Their theory is very little understood, and the attempts to improve them are still directed almost by chance." The purpose of science is so mankind can replace chance with certainty in matters relating to knowledge of the world around us. But the journey to such a catalogue of know-how is often not straightforward and that was certainly the case with the development of thermodynamics. A myriad of

scientists were involved. And to complicate matters even the unfolding of the ideas was not linear. A discovery would be made by one scientist and others after them would make further discoveries in other areas but regress in what the previous scientific thinker had uncovered. And so there was a mish-mash of ideas from different eras, with overall progress moving forwards at times, but thereafter regressing, only to be brought forward again by a unifying mind at a later stage. To show the see saw pattern of information in the development of thermodynamics, let us now correct Carnot's erroneous assertion about the true nature of heat by revisiting the genius of Emilie du Chatelet - who lived a century before him. For, many years before others ever recognized the fact,

she had declared two important properties about heat. First, heat is not an ether; secondly, that heat is the cause of movement among the particles that make up a body, entity or system. Here she is in her own words:

Thus, far from motion being the cause of fire, as some philosophers thought, fire is on the contrary the cause of the internal motion of the particles of all bodies

Emilie du Chatalet

This was an astounding mental achievement, accomplished against the grain of an overwhelming consensus in the opposite worldview. Take a moment to savour the mental prowess it demonstrates. She was here saying: instead of fire (heat) being a fluid ether that transmitted heat through its motion, as it moved from object to object, as for instance in caloric moving from the metal of the solid cannon being bored, into the water to make it boil, in Count Rumford's cannon experiment (as was the popular opinion), she was saying: No. Quite the opposite was happening.... She asserted that heat was not the result of motion (of a fluid ether), but that motion - the activity of atoms in elements and substances - was

the result of heat! So smart! And since all objects are made of atoms, they all had some heat within them! This was brilliant. Please take note too, that when the right model of reality comes along it is the exact opposite of what the ether based theories had proposed. This is why we say nature is counter-intuitive. This is also why no one has ever guessed how nature worked in the absence of experimental evidence - because nature is counter intuitive. You cannot get more counter intuitive than 1800 in the opposite direction! That is the history of scientific discovery once the data comes in. Du Chatelet came to a second

profound conclusion 200 years before Walther Nernst proposed the idea: no particle could exist without some movement due to heat, i.e., no particle can exist at absolute zero. Here is Emilie du Chatelet's original idea:

... Fire is perpetually antagonistic.... Thus, all in nature is in perpetual oscillations of dilation and contraction caused by the action of fire on bodies and the

reaction of bodies.... And we do not know of any perfectly hard bodies, because we do not know any that does not contain fire and the particles of which are in perfect

repose. Thus, the ancient philosophers who denied absolute rest, were surely more sensible, perhaps without knowing it, than those who denied motion

"

Emilie du Chatalet

"Fire is perpetually antagonistic!" What a sentence. It is one that we will lean on a little later to clarify another mystery about the nature of how our universe works. For now, we concentrate on the meaning of that phrase. An antagonist is an adversary or fighter against someone or something else. In saying fire is always antagonistic, she was saying fire never rests, it is always active, fighting. Since - by definition - no material substance can actually reach absolute zero, it means they all have some fire (heat) in them at all times. That in turn, means there would be something missing about our understanding of the world, if that understanding did not include an in-depth knowledge of the definition, scope and operation of the actitivies of heat. So true is

that statement that the field of study based on understanding how "energy" and "work," function in the universe is called thermodynamics. That is, the dynamics of heat! Our next scientist, Sir William Thomson, used that underlying principle, as captured in Carnot's original thesis about ideal heat engines, to theorise about the impossiblity of physical systems and entities actually reaching absolute zero. A temperature where there is no fire - or heat. Since temperature is one of the fundamental principles of thermodynamics, we will cover his work in that area - the development of the absolute zero temperature scale, that now bears his name. But he plays more than one role in establishing the science of thermodynamics. We will thus return

to him in another section to see how he influenced and was influenced by other great scientitists in the quickly shifting world of establishing the four laws of thermodynamics.

Understanding the Difficulty of Measuring Temperature

Since heat is the kinetic energy of many different particles, it cannot be measured directly. One must rather do so by reference to how that total collection of particles relates to another entity's particles - and only when they are at equilibrium. For if they are in thermal contact, but not at equilibrium, then the amount of motion in both will gradually correct until they both have the same amount of heat - or the same temperature. But at this point, we still do not know its exact value! Thus, we have to add a third system, and it is this system which we can call the temperature. However, for this third entity to accurately reflect the temperature - or the amount of heat - in each of the first two systems (since they will be at equilibrium),

it must also be in equilibrium with them. Otherwise, we get the same scenario of dynamic temperatures moving up or down to reach a state of common thermal equilibrium.

A quick tour of the history of how heat scales developed will make these challenges clear to everyone. We will start with the humble thermoscope, and move quickly through multiple stages of development until we get to the common Fahrenheit and Celsius scales we use today. In this process, we will come to realize the fundamental reason why an absolute, rather than operationally defined scale, was needed for scientific work. (I will define those terms shortly.) It is important to note that scientific work needs to be described universally, not by a system of local references.

Thermoscopes

1593

The effect of fire on its environment has long been recognized. Early on it was noticed that this effect extended to air. When air was heated up, it expanded. The ancient Greeks used "the general pneumatic principle of the thermoscope" in ancient Hellenistic times, says Wikipedia. It continues that: "It is thought, but not certain, that Galileo Galilei discovered the specific principle on which the device is based and built the first thermoscope in 1593." What is the difference then between thermocscopes, and our much more familiar thermometers? Thermoscopes, do not have a scale for the measurement of heat. Thermometers do. With thermoscopes, essentially, two containers were set up. One was an open jar containing water and the second, a glass bulb with a long tube

that ended in the water of the first container. The second container was full of air. The second container, the glass bulb was then heated, expanding the air inside it, which in turn caused air bubbles to disturb the water in the glass jar. When the temperature cooled, the air in the glass bulb would shrink in volume, causing water to be drawn up the long tube of the bulb. This very simple instrument could not tell temperature, only generally indicate when the environment was getting hotter, or colder. Of course, the ancient Greeks weren't operating in 1593, where our timeline starts. We choose that value, because it is the date Galileo Galilei is credited with the invention of the thermoscope by most sources.

Below is an example of a before and after diagram of how a thermoscope works. Notice that there are no markings for degrees.

The Art & Science of Temperature scales

And that was the problem. Thermoscopes had no markings and besides telling you that the temperature was generally hotter or generally cooler, they were not very useful. Especially, in the demanding field of accurate measurements that is science! But taking the next step, adding marking to such devices was not as straightforward as one might have imagined. Sir William Thomson a/k/a Lord Kelving explains:

The principle to be followed in constructing a thermometric scale might at first sight seem to be obvious, as it might appear that a perfect thermometer would indicate

equal additions of heat, as corresponding to equal elevations of temperature, estimated by the numbered divisions of its scale. It is however now recognized (from the

variations in the specific heats of bodies) as an experimentally demonstrated fact that thermometry under this condition is impossible, and we are left without any

principle on which to found an absolute thermometric scale

Lord Kelvin

Thermometers

1612

That was the year that an Italian named Santorio Santorio made the pivotal innovation that turned thermoscope technology into thermometer technology. He invented the scale. Though he might have been the first, he was by no means the only scientist to come up with this innovation. This immediately led to the problem of standardization, as each independent innovator of temperature scales had their own gauge, which measured the temperature differently from the others. Also, the reading one received depended on their location, as taking a reading at sea level would generate a different value than taking one high above sea level. There was thus, still work to be done before thermometers would be standardized and free from variable atmospheric

pressures.

1654

Ferdinando II de' Medici (14 July 1610 - 23 May 1670) was a man who loved technology and had the means as the Grand Duke of Tuscany to pursue his passion. Influenced by Galileo's dabbling into thermoscopes, he decided to try and make improvements to Galileo's earlier instrument. Galileo's thermoscopes did not operate with the highest precision, because as an open instrument, that is, an unsealed one, it was subject to differing atmospheric pressures, as dictated by varying weather conditions. Ferdinando solved this by sealing the bulb of his thermometer, which was accomplished by melting the glass at the end of its long tube so that the instrument was sealed and free from atmospheric variations.

His thermometer (because it also had a scale), produced in 1654, was thus a big improvement over the preceding efforts. Another advancement it had over Galileo's thermoscope is that, de' Medici used alcohol instead of water allowing the tube of his instrument to be much smaller than Galileo's. His thermometer was portable. There were several other scientists that continued work on improving thermometers, but the next real stage of progress came from one Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit.

The Development of Accurate Temperature Scales

The Fahrenheit Scale

The details for the development of the Fahrenheit scale are not well documented, but there are common threads through most variations of the accounts, and it is those threads that we will weave in outlining the establishment of thermometers. Daniel Gabriel Fahrenheit (1686 - 1736) had a groundbreaking impact on the design and manufacture of temperature scales, in that he was the first to use mercury as his agent of measurement. Calibrated scales (ones with markings for accurate measurement) were in use before Fahrenheit's many innovations to the field. One of the first, seems to be the one produced by famous astronomer, Ole Romer. In astronomy the number 60 features prominently. There are 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in a degree and 360

degrees in a full circle. These are some of the tools astronomists use to measure heavenly bodies. It was perhaps his familiarity with degrees of a circle that prompted Romer to choose 60 degrees as the basis for one of the reference points on his temperature scale. He set 60 degrees as the boiling point of water, which necessitated 7.5 degrees to be its freezing point. According to the calibration of his scale, body temperature then fell at 22.5 degrees.

Fahrenheit, had settled in The Hague and had been working as an accomplished glass blower by the time he met with Romer in 1708 and discovered the Romer thermometer - which he would use as the inspiration for his own temperature scale. He made gradual improvements to Romer's thermometer by substituting the much more appropriate fluid, mercury for alcohol. Mercury's boiling point is almost 4 times higher than alchohol's (674 degrees vs 173 degrees), meaning it can measure temperatures over a far greater range, before it evaporates. The limitations of using a scale with such a low boiling point: 173 degrees Fahrenheit, or 78.3 degrees Celsius, are obvious. Switching to mercury, allowed Fahrenheit to effectively multiply Romer's scale by a factor of 4. This enabled

thermometers to measure smaller and smaller temperature differences without the need for fractions. Hence, the first thing Fahrenheit did was round Romers reference numbers up. So, 7.5 degrees for the freezing point of water became 8 degrees, and body temperature went from 22.5 to 24 degrees. He manufactured these scales from 1714 to about 1724. Thereafter, he multiplied the whole scale by 4, which resulted in the key reference points on Fahrenheit's scales becoming: 32 degrees for the freezing point of water (8 x 4); and 96 degrees for body temperature (24 x 4). He found that water's boiling point arrived at 212 degrees Fahrenheit, and zero was determined by his formula for brine. It was this scale that Fahreheit proposed as the

Fahrenheit scale in 1724.

Why did Fahrenheit, choose to base his thermometer on Romer's? At the time scientists gauged the numbers on their scales arbitrarily, meaning each scale measured the same events differently. For instance, one thermometer's zero reading was based on the coldest day of the year in its inventors hometown. Romer's innovation was to base the gauging of his scale on empirical data from real world temperatures. Thus it could apply universally. Though thermometers had been greatly improved, there were still problems. The reference point of zero degrees Fahrenheit, corresponded to the temperature of a water, ice and salt mixture called a "brine," as it had previously, in Romer's thermometer, and in all the competing thermometers produced at that time. The problem with using

brine to define zero was that it was almost meaningless. Brine was a mixture of water, ice and salts, and varying thermometers used different salts to compose this mixture. Hence, each of the different salts - and thus scales - had varying temperatures, for what was supposed to be a standardized parameter. There was thus, no universal zero reference point. A firmer standard needed to be found!

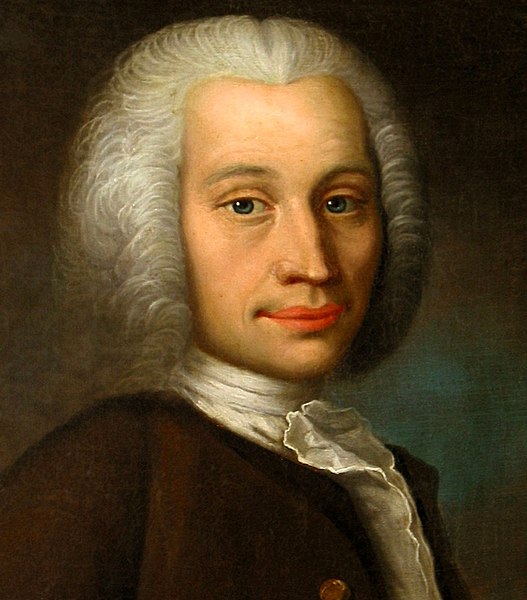

Anders Celsius & his Eponymous Scale

The contribution of Swedish astronomer Anders Celsius (27 November 1701 - 25 April 1744) was pivotal to the advancement of thermometry. In 1742 he proposed a scale that removed the inconsistent brine measurements from thermometers altogether, and calibrated their measurements around two central reference points, the freezing and boiling temperatures of water. All other normal daily activities would fall between those temperatures. His scale also used mercury, and so could reflect a similar range of values as Fahrenheit's, though it itself was limited to a spectrum of 100 degrees.

Lastly, while it came into wide usage over time, it was only in 1948 that this scale became the official Standard International unit of temperature. At that time it was renamed the Celsius scale having been called the Centigrade scale since its inception, as its range covered a 100 degrees. But now that thermometry, or the science of the measurement of temperature had been refined to such a great degree, what further need was there for another scale (the Kelvin scale)? The clue is in its definition as an absolute temperature scale, for whilst, the increase of temperatures could be accurately measured by the calibrated markings

on thermometers, there was a missing factor that was recognized - and solved - by our next innovators.

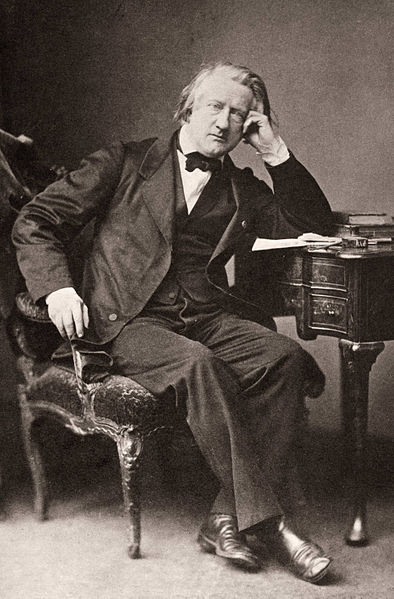

William Thomson a/k/a Lord Kelvin

Progress Continues - Finding the Absolute Variable

It was beneficial that physicists had managed to calibrate thermometers, but there was still a difficulty with their instrumentation. The fact that elements have different specific heats. Recall, that the measurement of temperature is not a direct measurement. Instead we measure temperature by calibrating the change in the properties of physical substances. At this point, that substance was mercury. However, mercury has a specific heat which is different to other elements, meaning, the rate at which heat affects it is different to the rate at which heat would affect another element. This complicated how to increment the markings used to measure temperature, as each element would then need its own scale! Hence,

the next refinement in thermometry had to be a decoupling of temperature measurement from calibrating the change in the properties of some material substance or element. The calibration of heat had to be removed from this or that element, and come to be based on a variable of nature that all elements shared due to the laws of thermodynamics. Understanding this was a big mental shift and displayed a clear understanding of how heat affects all elements and molecules.

EXPLANATORY NOTE:

William Thomson was a man who received many plaudits in his life. Some, included titles for his many scientific achievements. In England these often meant changing his name. He thus went from being William Thomson to Sir William Thomson, and later yet, to Lord Kelvin. Lord Kelvin was a title he gained much later in his life, but came to be the name he is most recognized by. Since much of his scientific work happened before he received this honour, it took place when he was either just William Thomson, or Sir William Thomson. For that reason, I will always refer to him as William Thomson when describing his work, but as Lord Kelvin in quotes.

It is at this point that our next great mind comes into focus, William Thomson. We have heard much about him already because his fingerprints are all over different developments in the establishment of thermodynamics. Let us now meet him formally. William Thomson was a young mathematical genius born in Belfast in Northern Ireland. Charming and likable, unlike most scientists he was popular throughout his entire professional life. Being mentioned in one of his papers meant instant recognition for people, whether they were scientists or laymen. It was Thomson who popularized Carnot's theories on heat. It was Thomson whose mention

of Joule's experiments, caused Joule to reach out to him and start a collaboration that would yield wonderful results! And it was Thomson who innovated the correct approach uncovering the hidden variable that would help mankind develop a theoretical scale for absolute zero. In the development of this absolute framework, he identified a problem:

Next in importance to the primary establishment of an absolute scale, independently of the properties of any particular kind of matter, is the fixing upon an

arbitrary system of thermometry, according to which results of observations made by different experimenters, in various positions and circumstances, may be exactly

compared

Lord Kelvin

Different experimenters, including Henri Victor Regnault - who had become a big influence on Kelvin - had been testing the qualities of, and using air as the medium, which might be best suited to the needs of thermometry. This, as Kelvin noted, produced thermometers that were "least liable to uncertain variations of any kind."

Additionally, up until this point, thermometers were set according to "operational" definitions. The Imperial standard used in the United States and the Metric system used, by and large, in the rest of the world (with a few exceptions) are examples of systems based on operational definitions. A term that really means the value is determined by how humans define it. They are arbitrary units. What scientists were looking for was a value that nature set, so that it could be a universal parameter - an absolute temperature scale. What was needed was a universal standard of absolute measurement. As yet, thermometers were set according to parameters based on the

freezing and boiling points of water. We have learned previously that all substances have unique boiling and freezing points, just as they have unique heat capacities. The question was: could a thermometer be devised such that its zero designation would represent the point where ALL substances and elements could be defined by the same parameter? Talk of an absolute scale, which would have zero representing the coldest possible temperature, the temperature at which the kinetic energy of ALL SUBSTANNCES AND ELEMENTS WOULD BE ZERO had been mulled by scientists for a while. The problem was no one knew how to construct one - until ...

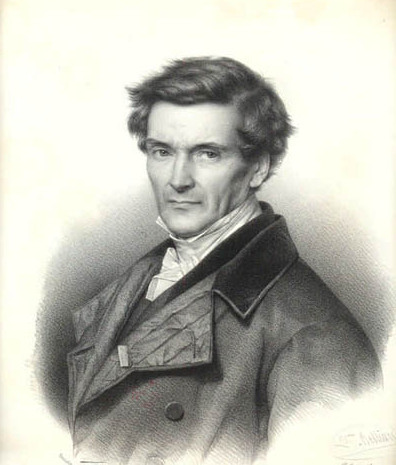

Henri Victor Regnault

Every Neo needs a Morpheus. Lord Kelvin was a man who was influenced by many people, but the one who was most influential in helping him to establish the principles of an absolute temperateure scale was Victor Regnault (21 July 1810 - 19 January 1878). Regnault's contribution to the field of thermodynamics came from his extensive work on the thermal properties of matter. Like Brahe, so many centuries before him, Regnault was a meticulous scientist who compiled extensive numerical tables in his chosen area of study - the properties of steam! The publication of his tables in 1847, led to many honours in quick succession, including the Rumford metal. Interesting how yesterday's mavericks become tomorrow's standard of excellence. An expert on the thermal properties of

matter, Regnault was able to innovate many sensitive instruments including calorimeters, hygrometers, hypsometers and thermometers. These enabled him to measure the specific heats of different substances, but more importantly the coefficient of thermal expansion of gases!

As the name suggests, the coefficient of thermal expansion is the effect that temperature has on the volume of a gas. If the temperature is increased, the speed of the molecules of the gas increases, and the gas expands its volume (area it covers), if it's in an open system (open environment); or its pressure, if it's in a closed system, such as a container. That value for an ideal gas proved to be 1/273.15 per 0C, which is approximately equal to 0.00366 per 0C. How did this affect gases as they cooled? It caused a: "fractional change in size per degree change in temperature, at a constant pressure, such that lower coefficients describe lower propensity for change in size." Now gases always expand to fill the

container in which they are found. And something unique happens when that container remains at a constant volume as the gas is either heated or cooled. In such a case, the parameter that changes is not the volume (as the size of the container is constant, by definition), but their pressure! The hotter the gas, the higher its resultant pressure, as its molecules or atoms are hitting the inside of the container with greater force (that's what creates pressure). In the case where the gas is cooled, its individual particles move slower and with less force, and thus the pressure on the inside of that container decreases. Thus, identifying the pressure of an unchanging volume of gas proved to greatly simplify experiments, and made interpreting

their results that much easier. This, was Thomson's methodology Thomson adopted. To be sure, the concept of absolute zero was known before him, but over the years different scientists had proposed differing values all of which were wrong. It was Lord Kelvin who would crack that code, and for this reason the measurement of absolute temperatures - the only scale used for scientific work - are stated in kelvin. Thus -273.15 degrees C, is 0 kelvin.

Let us now touch on the simple methodology behind how William Thomson derived the number -273.15 degrees Celsius. Once the data is in, and if we are in possession of the right model of reality, arriving at correct conclusions is relatively straighforward. Thomson used two foundational papers to arrive at his conclusion: Sadi Carnot's seminal work and Regnault's immaculate tables. Like Kepler using Nicolaus Copernicus' thesis on heliocentricity and Tycho Brahe's extensive data catalogue, Thomson determined in an 1848 paper entitled On an Absolute Thermometric Scale Founded on Carnot's Theory of the Motive Power of Heat, and Calculated from Regnault's Observations, that:

This is what we might anticipate, when we reflect that infinite cold must correspond to a finite number of degrees of the air-thermometer below zero; since, if we

push the strict principle of graduation ... sufficiently far, we should arrive at a point corresponding to the volume of air being reduced to nothing, which would

be marked as -2730 of the scale (-100/.366, if .366 be the coefficient of expansion); and therefore -2730 of

the air-thermometer is a point which cannot be reached at any finite temperature, however low

"

William Thomson

He understood intimately the underlying principle of Carnot's work: that systems needed heat to function. What he was doing was setting himself the task of finding the theoretical limit at which everything in physics would stop functioning because it had no heat. What temperature might that be? On his search he was guided by the Tycho-Brahe-like calculations of Regnault who had observed that as temperatures cooled the distance between particles of gases decreased. He wisely combined these two observations in a novel new way. Realizing that gases have different parameters or variables by which they can be measured. Scientists had already seen that if you held the volume constant as you dropped the temperature, the gas would

decrease in pressure according to a set pattern. Part of these observations was noting the rate of this decrease in pressure at lower and lower temperatures. At zero degrees Celsius the loss in pressure was about 1/273 for every degree Celsius of cooling. As scientists couldn't yet create very low temperatures, they extended the effects of these cooling experiments theoretically (mentally). Following this pattern, there would be a temperature below zero degrees Celsius at which the pressure - not the volume - but the pressure of the gas would theoretically fall to zero. What temperature would that be? Well, 1/273 - the rate of decrease in pressure per degree of cooling - equals 0.00366. Since he was testing temperatures

below zero degrees Celsius, he chose a temperature range of 0 to -1000C. Dividing the fractional change in pressure over that entire negative 100 degree range by the numerator of -100 produced the formula: -100/.366, which equalled about -273: or absolute zero. The theoretical temperature that no entity in physics could reach. In the end absolute zero proved to be -273.15, but William Thomson had managed to crack the code and to give mankind a standard that no physical element or system could reach. This set a vital parameter for the operational scope of thermodynamics.

The developments of thermoscopes, thermometers, and ultimately the absolute thermodynamic scale teach us two important points by forming the foundations of two laws of thermodynamics. First, they teach us that unlike the first and second laws of thermodynamics, which have been our main focus, the other two laws are not operational. In other words, they don't tell us about how thermodynamics guides the processes of the universe, they are more definitions of what is impossible in thermodynamic terms. The third law sets an impossible limit no physical entity can reach. And the zeroth law merely defines how we measure temperature. Thus understanding thermodynamics is really about grasping its first and second laws. That is where all action is. The other two laws merely